BY Robyn Kelton, MA and Irina Tenis, PhD | June 12, 2025

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Institute for Early Childhood.

By Robyn Kelton, M.A. and Irina Tenis, Ph.D. | June 12, 2025

INTRODUCTION

The early childhood education (ECE) workforce is diverse, encompassing professionals operating in various settings and under varying conditions. Among these, child care center directors and family child care (FCC) professionals—those who own and operate home-based child care programs—represent two critical groups of leaders who play pivotal roles in shaping the quality of children’s early learning experiences. Both groups function as administrators, responsible for delivering high-quality programming, ensuring compliance with licensing and regulatory standards, managing staff, and fostering relationships with families.

While their overarching goals often align, the day-to-day realities of their roles differ in many meaningful ways. Center directors typically manage larger teams and multi-classroom programs within formal organizational systems, whereas FCC professionals often operate as sole proprietors, balancing the role of mixed-age group educator and business owner with administrative duties and non-traditional working hours in a home-based setting (Bromer et al., 2021; Hooper et al., 2019; Kelton & Tenis, 2024; Porter & Reiman, 2016). These structural differences shape not only their work experiences but also their professional needs and identities.

Recognizing the commonalities and distinctions between these roles is essential to understanding the workforce and informing tailored workforce supports and professional development strategies. Moreover, understanding the perspectives of the administrators themselves is critical. This research brief contributes to those efforts by examining data from licensed FCC professionals and center-based administrators in Illinois, comparing their career motivations, job satisfaction, commitment, and self-efficacy across key leadership competencies.

METHOD

This study analyzed data from two distinct samples. The first included 89 FCC professionals who owned and operated FCC programs, and the second included 85 center-based administrators. All participants worked in licensed early childhood programs in Illinois. Data were collected as part of the registration process for various leadership academies hosted by the McCormick Institute’s Center for Early Childhood Leadership, prior to the start of the academies, between 2022 and 2025.

Although each sample is reasonably robust, caution should be used when generalizing findings, as participants were not selected through random sampling but were instead individuals enrolled in leadership academies.

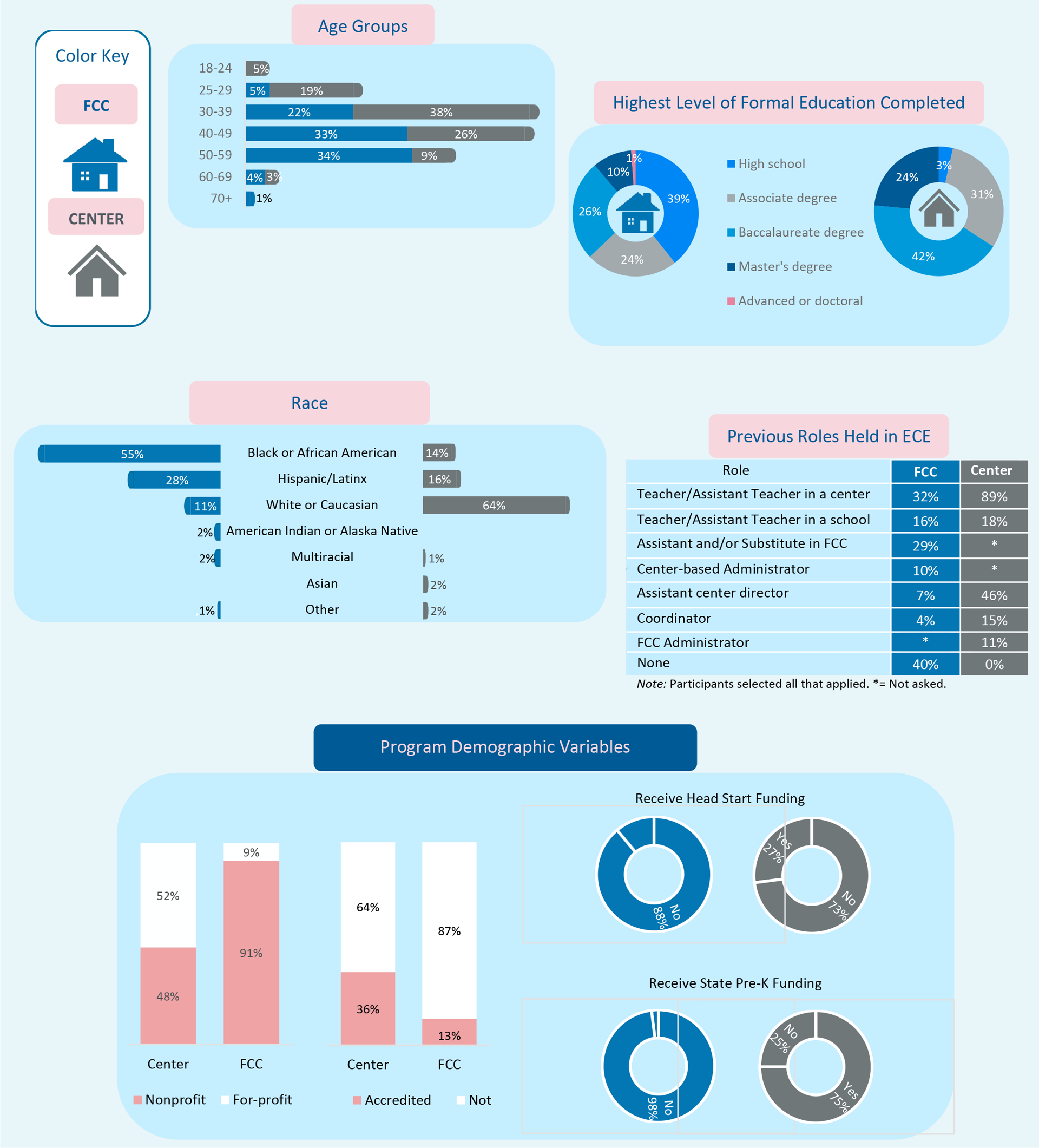

Samples. Broadly, both groups had similar years of experience in the ECE field. On average, FCC administrators had 13 years of experience (range less than 1 year to 35 years), while center administrators also averaged 13 years of experience in the field (range 1 to 36 years). Both groups were generally well-educated, but the FCC sample had a smaller percentage of participants without degrees. Notably, 74% of FCC professionals without a degree had completed some college coursework. Twenty-eight percent of center-based administrators held an administrator or director credential, compared to 27% of FCC professionals who held an FCC credential.

The infographics below provide further demographic comparisons between the two samples, including age, race, and educational background. While differences in variables collected limited the ability to make direct program-level comparisons, a few overlapping variables revealed meaningful distinctions in program auspice, funding, and operating models, and accreditation status. These findings are also highlighted in the infographic section.

Measures. Data were collected using two tailored versions of the Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS): the ARPS, designed for center-based administrators, and the ARPS–Home Based (ARPS-HB) for FCC professionals (Bella et al., 2017; Bella & Kelton, 2021). Both surveys are administered online and take approximately 25 minutes to complete. They assess alignment between current and ideal work experiences, past perspectives, current role perceptions, self-efficacy levels, and mastery perceptions.

FINDINGS

Below are key findings regarding similarities and differences between home-based and center-based administrators. Career motivation, satisfaction, and commitment are explored, and confidence levels in leadership competencies are compared.

Career Motivation, Satisfaction, and Commitment

Our previous research has identified differences in the motivations of FCC professionals and center directors for pursuing administrative roles (Kelton & Tenis, 2024; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018), and this study replicates those findings. Center directors most often enter administration through a professionalized pathway, shaped by encouragement from others and hierarchical organizational structures. In this sample, 86% of center directors had prior experience teaching in an ECE program, K-12 school, or both, consistent with previous findings that directors are often promoted from teaching positions.

In contrast, FCC professionals most frequently cited self-driven, family-oriented, or entrepreneurial motivations for entering administration. Prior research has also found that FCC administrators’ strong sense of work autonomy is linked to higher engagement and commitment (Kelton & Tenis, 2024; Lee et al., 2019).

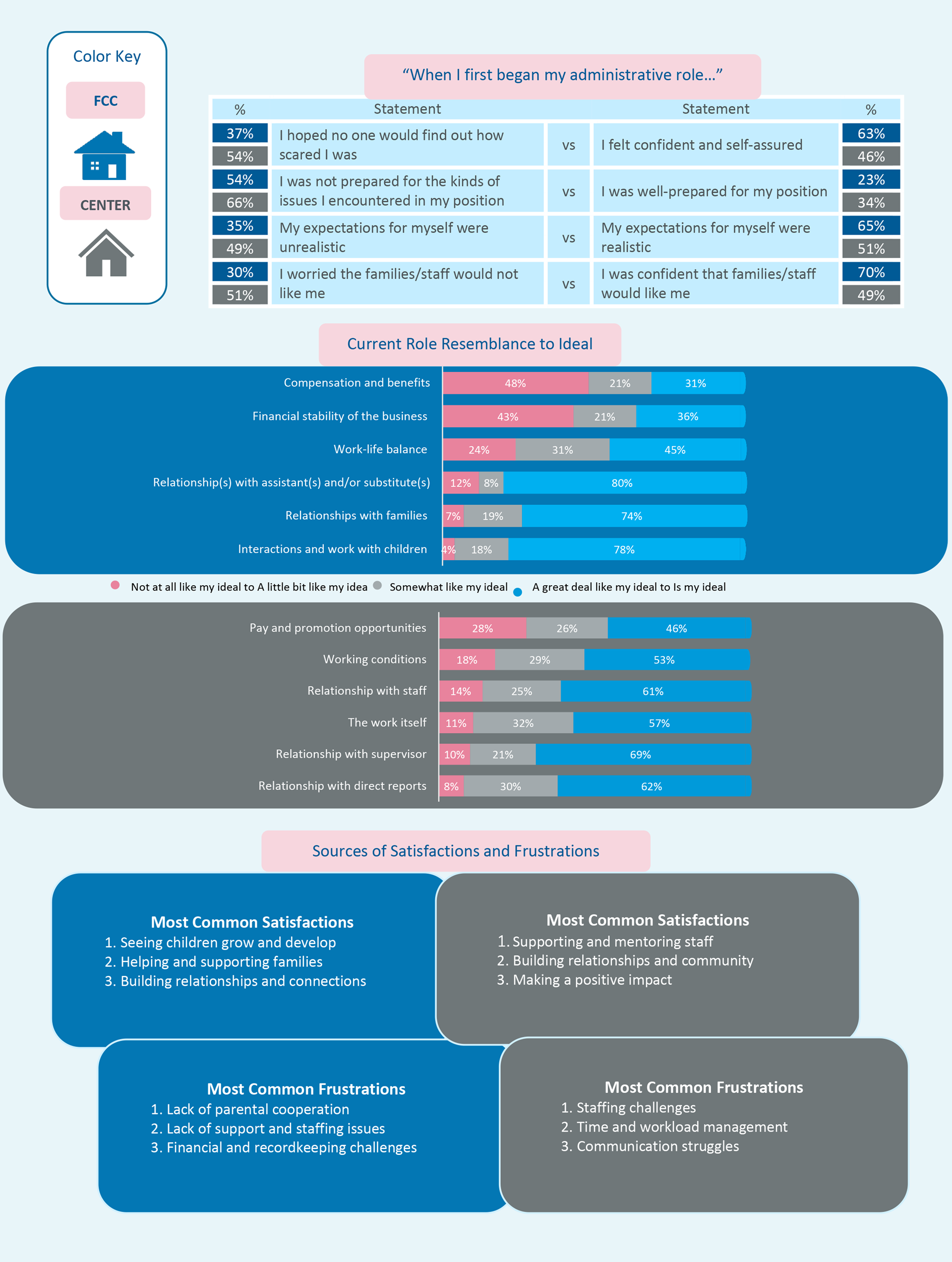

The ARPS and ARPS-HB asked participants to reflect on their initial experiences and perceptions when stepping into administrative roles. Understanding these career trajectories is essential for designing leadership development opportunities that reflect the operational realities of each role and the motivations and professional identities of the individuals in them.

Role perception and job satisfaction have been shown to influence behavior and to be critical indicators of both performance and commitment (e.g., Hogg et al., 1995; Bloom, 2010; Wagner & French, 2009). Both groups were asked to rate on a Likert scale how well elements of their work aligned with their ideals (0 = not at all like my ideal, to 5 = is my ideal) and were asked to share their greatest areas of satisfaction and frustration. As demonstrated in the figures below, both groups experience high alignment and satisfaction in the relational aspects of their roles, and they also share concerns about compensation, stability, and professional growth. In terms of frustrations, both groups commonly noted hindrances around staffing. However, the differences between the groups may reflect FCC administrators’ concerns about the overall sustainability and structure of the program. In contrast, center directors’ concerns focus more on the complexities of managing a larger team.

Last, indicators of commitment trended slightly higher for FCC with a statistically significant difference in only one area: FCC administrators reported significantly higher levels of pride in the work (M = .88,

SD = .33) than center administrators (M = .73,

SD = .45;

t(151) = 2.32,

p < .05).

Self-Efficacy Across Leadership Competencies

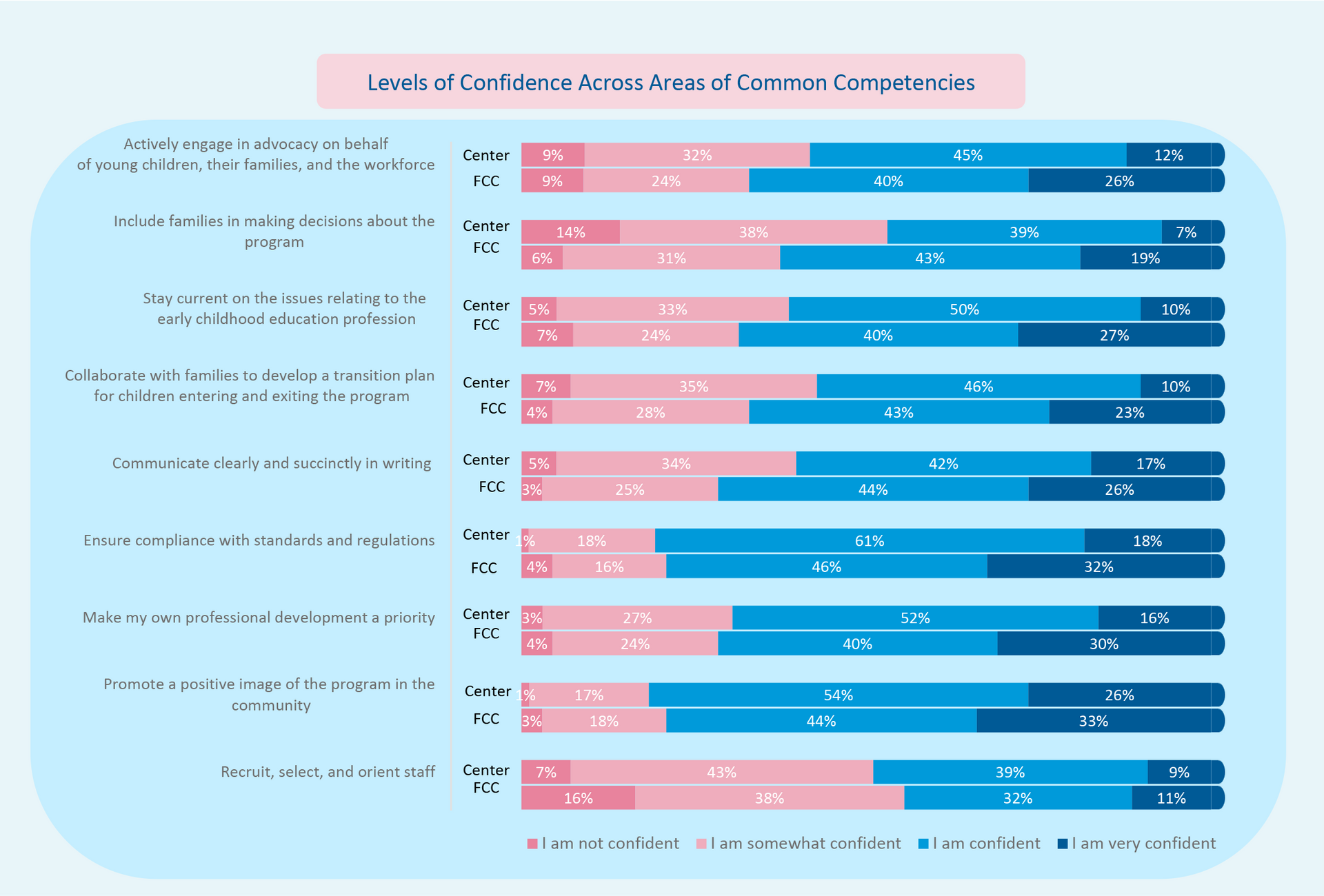

One additional area of research interest was exploring differences and similarities in self-efficacy between FCC and center-based administrators across similar competencies. In both the ARPS and the ARPS-HB, respondents ranked their current level of confidence across 36 (ARPS) or 28 (ARPS-HB) specific competencies related to ECE administration. Each question was scored on a four-point Likert scale (1 = I am not confident in my ability, 2 = I am somewhat confident in my ability, 3 = I am confident in my ability, 4 = I am very confident in my ability).

Given the unique demands of each role, many of the competencies differed between the two surveys. Notably, the highest- and lowest-rated areas of confidence also varied somewhat by group. FCC administrators reported the greatest confidence in working with mixed-age groups, promoting a positive program image in the community, and ensuring regulatory compliance. They reported the least confidence in financial management, using program assessment data for continuous quality improvement, and marketing to prospective clients. Center administrators, on the other hand, reported the highest confidence in building partnerships with families, promoting a positive program image, and modeling best practices for teaching staff. Their lowest confidence areas were developing and managing program finances, implementing equitable salary scales, and working with stakeholders to create a shared vision and priorities. Despite their differences, both groups showed high confidence in promoting their programs and lower confidence in financial-related competencies. Nine competencies directly overlapped across both surveys. While there were minor variations in mean scores among those nine areas, none of the differences were statistically significant. The infographic below illustrates how FCC and center administrators rated their confidence across these shared competencies.

DISCUSSION

Although both FCC and center-based administrators engage in similar leadership domains, the context in which they apply these competencies varies significantly. FCC administrators typically work alone, balancing education and care with business and entrepreneurial tasks, while center administrators tend to operate within larger and more complex organizational systems. These structural and contextual differences shape what leadership looks like in each setting and where individuals feel most—and least—confident.

This study reinforces that while administrators across settings may share some strengths and challenges, such as confidence in promoting their programs or struggles with financial management, their leadership experiences are deeply influenced by their operational realities. FCC leaders, for example, may feel isolated in their role, with limited access to peer networks or systems of support (Bromer et al., 2021). Center administrators, meanwhile, often navigate team dynamics, staff supervision, and institutional policies.

Given these differences, a one-size-fits-all model for leadership development is unlikely to be effective. While many leadership competencies are shared, their application—and the supports needed to build them—vary widely. Professional development initiatives must be context-responsive, honoring the motivations, structures, and day-to-day demands unique to each leadership role. Tailoring supports in this way is essential for strengthening leadership capacity and ultimately improving outcomes across the diverse early childhood education landscape.

REFERENCES

Amadon, S., Lin, Y-C., Padilla, C., M. (2023). Turnover in the Center-based Child Care and Early Education Workforce: Findings from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education. OPRE Report #2023-061. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Bella, J., Abel, M., Bloom, P.J., & Talan, T. (2017). Administrator Role Perception Survey. McCormick Institute Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bella, J., & Kelton, R. (2018). Administrator Role Perception Survey—Home-Based. McCormick Institute Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bloom, P. J. (2010). Measuring work attitudes in the early childhood setting: Technical manual for the Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey and the Early Childhood Work Environment Survey. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

Bromer, J., Melvin, S., Porter, T., & Ragonese-Barnes, M. (2021). The shifting supply of regulated family child care in the U.S.: A literature review and conceptual model. Chicago, IL: Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute.

Hogg, M. A., Deborah J. T., and M. K. (1995). A Tale of Two Theories: A Critical Comparison of Identity Theory with Social Identity Theory Author (S). Social Psychology Quarterly. Vol. 58:(4) 255–269.

Hooper, A., Hallam, R., & Skrobot, C. (2019). “Our quality is a little bit different”: How family childcare providers who participate in a Quality Rating and Improvement System and receive childcare subsidy define quality. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 22(1), 76-94.

Kelton, R. & Tenis, I. (2024). Family Child Care Professionals: Understanding a Critical Workforce. Research Notes. McCormick Institute Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership (2018). Directors’ professional development needs differ by developmental stage. Research Notes. National Louis University.

Porter, T., & Reiman, K. (2016). Examining quality in family child care: An evaluation of All Our Kin. New Haven, CT: All Our Kin.

van der Meer, J., Vermeeren, B., & Steijn, B. (2023). Why do Role Perceptions Matter? A Qualitative Study on Role Conflicts and the Coping Behavior of Dutch Municipal Enforcement Officers. Urban Affairs Review, 60(2), 640-673.

Totenhagen, C. J., Hawkins, S. A., Casper, D. M., Bosch, L. A., Hawkey, K. R., & Borden, L. M. (2016). Retaining Early Childhood Education Workers: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(4), 585–599.

Wagner, B. D., & French, L. (2010). Motivation, Work Satisfaction, and Teacher Change Among Early Childhood Teachers. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 24(2), 152–171.