BY Michael B. Abel | September 26, 2017

Sim Loh is a family partnership coordinator at Children’s Village, a nationally-accredited Keystone 4 STARS early learning and school-age enrichment program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, serving about 350 children. She supports children and families, including non-English speaking families of immigrant status, by ensuring equitable access to education, health, employment, and legal information and resources on a day-to-day basis. She is a member of the Children First Racial Equity Early Childhood Education Provider Council, a community member representative of Philadelphia School District Multilingual Advisory Council, and a board member of Historic Philadelphia.

Sim explains, “I ensure families know their rights and educate them on ways to speak up for themselves and request for interpretation/translation services. I share families’ stories and experiences with legislators and decision-makers so that their needs are understood. Attending Leadership Connections will help me strengthen and grow my skills in all domains by interacting with and hearing from experienced leaders in different positions. With newly acquired skills, I seek to learn about the systems level while paying close attention to the accessibility and barriers of different systems and resources and their impacts on young children and their families.”

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally featured in the Summer 2017 edition of Kansas Child Magazine, a publication of Child Care Aware of Kansas.

FOR DECADES, the value of partnering with families to support children’s learning and development has been touted among early childhood care and education leaders. Initiatives to enhance family engagement in early childhood programs and schools is increasingly prevalent, and with good reason. Family engagement increases children’s age-appropriate cognitive skills (Roggman, Boyce, and Cook, 2009), improves student achievement (Forry, Bromer, Chrisler, Rothenber, Simkin, and Danieri, 2012; McWayne, Hampton, Fantuzzo, Cohen, & Sekino, 2004), and supports early literacy in diverse families (Barrueco, Smith, and Stephens, 2015).

Involving parents and other family members in the learning opportunities that occur in child care settings and building bridges between the home and the program extend learning and promote child development in a meaningful and authentic way.

Early childhood administrators might feel unprepared to lead efforts that foster family engagement. However, being intentional about involving families in program activities and choosing to consider family members’ perspectives in decision-making go a long way towardovercoming any reticence the leader might have about reaching out to families. A shift in the leaders’ thinking aids in creating an organizational culture that welcomes family partnerships.

Leadership for family engagement might include creating policies and practices that respect differing family structures, involving family members in decisions related to their children, and regularly asking for feedback from family members about their experiences with the program. Directors who make family engagement a priority actively seek parents’ and extended family members’ support and assistance. They also encourage staff to allow families easy access to the classroom and school. Supervisors can urge teachers to make families a visible presence in their classrooms by posting photos or displaying artifacts from children’s experiences outside of the program (Pelo 2002).

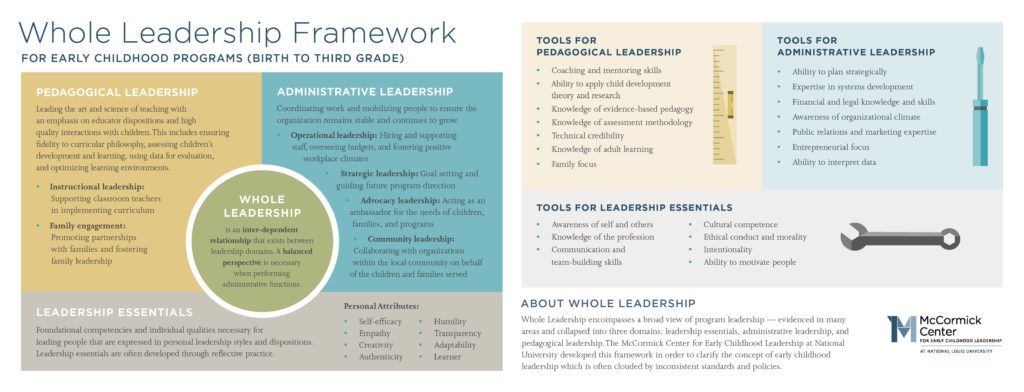

Encouraging teachers to bring family life into the classroom is a function of the administrator exercising pedagogical leadership. The McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University recently developed the Whole Leadership Framework to clarify and differentiate various aspects of leadership in early childhood programs (Abel, Talan, Masterson, 2017). This broad view of leadership can be explained through three domains: leadership essentials, administrative leadership, and pedagogical leadership.

Leadership essentials include foundational skills in reflective practice, communication, and relationship-building. They include such personal attributes as self-efficacy, empathy, creativity, authenticity, humility, transparency, adaptability, and a learner’s perspective on which administrative and pedagogical leadership are built and are often expressed in leadership styles and dispositions. Leadership essentials are foundational for influencing and motivating people around a shared vision.

Administrative leadership involves maximizing capacity to develop and sustain an early childhood organization. It is about setting goals, orchestrating work, and mobilizing people to sustain an early childhood organization, with both operational and strategic leadership functions. Operational leadership is accomplished through such critical functions as hiring, evaluating, and supporting teaching staff; developing budgets aligned with program goals and needs; and maintaining a positive organizational culture and climate. Strategic leadership involves guiding the direction of an early childhood organization with the future in mind. Strategic leaders clarify mission and values, inspire staff to pursue a shared vision, and ensure that program goals and outcomes are attained. Effective administrative leaders establish systems for consistent implementation of program operations to meet the needs of children, families, and staff.

Pedagogical leadership involves supporting the art and science of teaching, including ensuring high-quality interactions with children and affecting the dispositions of teachers. Pedagogical leadership includes instructional leadership and family engagement. As pedagogical leaders, directors continually assess whether classroom activities are implemented with fidelity to the program’s philosophy and curricular objectives. They examine the learning environment from the child’s perspective and consider whether it is authentic to their life beyond the classroom, and inclusive of families’ cultures. Is it provocative enough to capture children’s interests and challenging enough to affect their development? Pedagogical leaders also create systems of accountability for assessing children’s development and learning, using evaluation data to guide and differentiate instruction, and optimizing learning environments.

Instructional leadership in an early care and education setting involves establishing and maintaining an organizational culture that functions as a learning community. Program leaders attend to teaching and learning as the primary focus of the program and make it a priority in their work. As instructional leaders, directors can affect classroom practices by establishing peer learning teams, increasing awareness of emerging pedagogical methods, and allocating resources for professional development. Reflective supervision can support child development and learning by providing feedback to teachers about their practice and drawing attention to the children’s individual needs. Fostering an organizational culture that values reflection and continuous improvement is a powerful tool for effective instructional leaders.

Engaging families to support children’s learning and development requires leadership and organizational focus.

In tandem with establishing a community of learners among staff, pedagogical leadership requires including families in the process. When administrators acknowledge the primary role of parents and family members in their children’s learning and development, it influences the program’s pedagogical approach. The director’s role in shaping expectations for family engagement and establishing an organizational climate that supports families’ participation in learning activities is critical. Hilado, Kallemeyn, and Phillips (2013) found that administrators who had a more flexible definition of family involvement tended to have more positive views of parents and perceived higher levels of involvement. Bornfreund (2014) emphasizes that random acts of encouraging family involvement aren’t enough. Simply inviting parents to center celebrations, distributing a newsletter, or creating a parent resource room is not likely to lead to improved outcomes for children.

Pedagogical leadership that affects children’s learning and development requires establishing family-center partnerships where power and responsibility are shared. It can be challenging to shift attitudes and perspectives within an organization to embrace a philosophy that families are central in the learning equation, but effective leaders are able to articulate a vision for partnering with families and manage change processes that influence the collective core beliefs about shared responsibility for children’s learning. Ongoing individualized communication, home visits, and multiple opportunities for families to be involved in the life of the program and classroom can aid in changing the organizational culture with regard to family engagement.

It is important to recognize that the domains of Whole Leadership — Leadership Essentials, Administrative Leadership, and Pedagogical Leadership — do not operate independently. Few leadership roles and functions are mutually exclusive. Rather, leadership exercised in one domain affects and/or requires reciprocal leadership in the other domains. Administrative and pedagogical leadership are separate but connected. The interdependent relationship between the domains is vital to organizational success, especially as it relates to family engagement. Implementing family engagement efforts that affect teaching and learning requires strategic and operational leadership, such as planning for coordinated and aligned activities, establishing objectives for shared decision-making, and allocating resources to involve families. It is through a balanced approach to leadership that family engagement can flourish.

Michael B. Abel is the Director of Research and Evaluation at the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University where he designs and implements original research studies regarding administrative practice in early childhood programs. His education includes an Interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Educational Leadership Policy and Foundations, an M.A. in Educational Administration, and an M.A. in Early Childhood Education. Mike has extensive experience in higher education, child care management, and service with NAEYC.