The Relationship between Global Classroom and Administrative Quality: A Cross-Cultural Comparison

BY McCormick Center | February 22, 2022

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

International comparative education studies contribute to improvements in education systems by highlighting strengths and identifying challenges found in the different cultural contexts of different countries. Comparative early childhood education (ECE) studies provide new ideas and insights into how local and national systems can be improved. There are, however, few comparative international ECE studies that report data collected at the individual program level (Li, 2015; Sheridan et al., 2009). Further, there is scant research that examines the relationship between administrative practices and classroom practices in ECE programs (Lower and Cassidy, 2007; McCormick, 2010a; McCormick, 2010b).

Quality improvement systems in ECE exist in many countries (OECD, 2015). In the United States, 49 states have or are developing a quality rating and improvement system (QRIS). Dilara Yaya-Bryson, Catherine Scott-Little, and Deborah Cassidy, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and Berrin Akman, a researcher at Hacettepe University, in Ankara, Turkey, examined the quality of programs in two ECE quality improvement systems, one in Turkey and one in North Carolina, USA (Yaya-Bryson et al., 2020). In this study, the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2005) was used to evaluate the quality of the early childhood classrooms, and the Program Administration Scale (Talan and Bloom, 2004) was used to evaluate the quality of administrative practices.

Cultural Context of Study

The two ECE quality improvement systems included in this research differed in several key areas, including the auspice of the system, the length of time the system had been in place, and the degree to which standards for program quality were developed.

Turkey

The centralized early childhood system in Turkey is administered by the Ministry of National Education. The regulation of ECE programs began in the 1960s, with new standards published in 2015. At the time the research was conducted, these standards had not been empirically tested.

North Carolina

The United States utilizes a state-based early childhood system of quality monitoring and improvement. The QRIS in North Carolina, the Star Rated License System, has been operating since 1999. It includes ongoing quality assessments using the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R) and other instruments to award a Star Rated License rating of 1 to 5 stars for all regulated early care and education programs in the state.

The purpose of the study was to compare the quality of programs in two different early childhood systems—Turkey, a developing country with emerging standards for quality early childhood education, and North Carolina, a state with a well-established quality improvement system for early care and education programs.

Methods

The sample for the study included 40 ECE programs, 20 located in Turkey and 20 located in North Carolina. In each program, one classroom serving preschool-aged children was selected using convenience sampling for observation using the ECERS-R. The director of each program was interviewed based on the 25 items of the Program Administration Scale (PAS). Documentation from the program was reviewed immediately following the interview to verify the director’s responses to interview questions.

Overall, the auspice of the program and the qualifications of the staff differed between the Turkey and North Carolina sample programs. There were more public programs in the Turkish sample (70%) than in the North Carolina sample (5%). In Turkey, the vast majority (95%) of directors had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while in North Carolina, a majority (60%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher. A similar pattern was seen with teacher qualifications. In Turkey, 85% of observed teachers had at least a bachelor’s degree; in North Carolina, 40% of observed teachers had at least a bachelor’s degree.

Pilot studies were conducted prior to collecting data with the PAS. Co-raters selected to collect data with the ECERS-R in Turkey were trained to administer the PAS using the translated version (Kalkan and Akman, 2009). The primary researcher and three other trained raters administered the PAS for the pilot in Turkey. Inter-rater reliability for the Turkish co-raters was calculated as .98. In North Carolina, the primary researcher and a reliable PAS assessor conducted assessments in a pilot study. Inter-rater reliability for the PAS was computed as .92.

The ECERS-R and the PAS were administered by a primary researcher on the same day, with the classroom observation occurring in the morning and the director interview and documentation review occurring in the afternoon. Independent t-tests were used to compare ECERS-R and PAS scores from the programs in Turkey with scores from programs in North Carolina. Pearson correlations between ECERS-R and PAS total scores were determined and used for comparison to see if there were significant differences between correlations for the scores from programs in each of the cultural contexts.

Findings

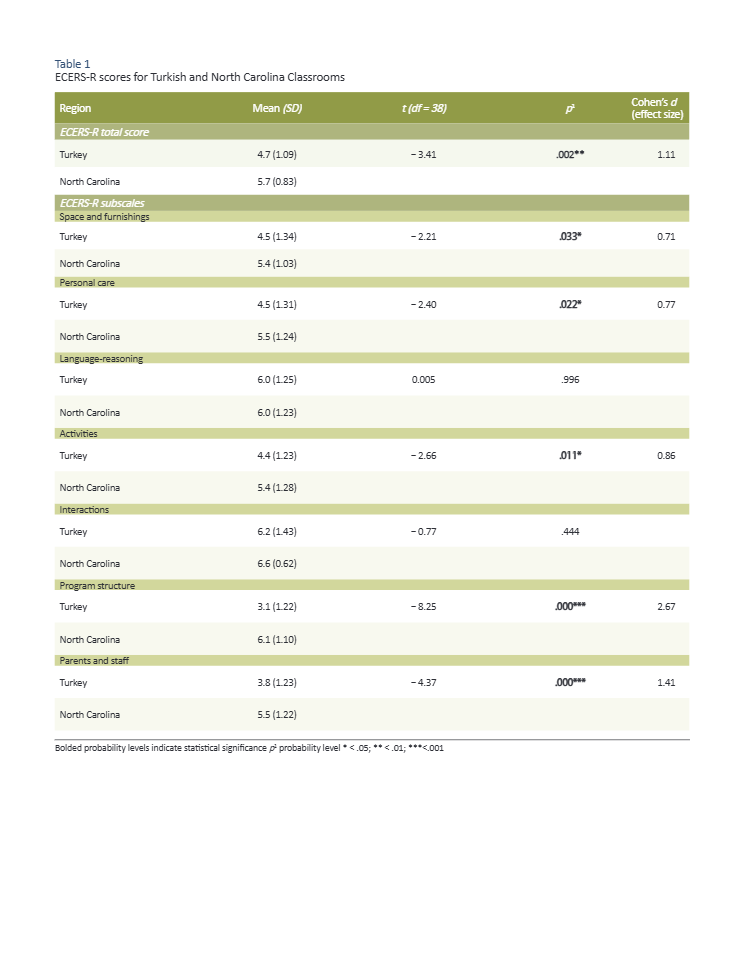

Table 1 provides descriptive data on ECERS-R scores for classroom quality in which the t-test comparisons are reported as well as effect sizes using Cohen’s d. The overall mean score on ECERS-R in Turkey (M = 4.7, SD = 1.09) was significantly lower than the overall mean score for North Carolina (M = 5.7, SD = .83), t = -3.41. p = .002. The mean score for North Carolina is in the good range on the rating scale (1 = inadequate to 7 = excellent). The mean score for Turkey was in the medium range, falling between minimal and good on the rating scale.

For the total PAS scores on the quality of administrative practices, the t-test comparison between Turkey (M = 3.5, SD = .94) and North Carolina (M = 3.3, SD = .95) was not significant, t = .467, p = .643. Mean scores for Turkey and North Carolina on each PAS subscale fell within a low to medium range (1 is inadequate to 7 is excellent). There were no significant differences between national contexts on any of the PAS subscales.

An additional purpose of the study was to explore the associations in the overall ratings of classroom environment quality and administrative quality in each quality improvement system. Pearson correlations were used to evaluate the strength of the relationship between the overall ECERS-R score and overall PAS score in each system. In Turkey, there was a significant correlation between ECERS-R and PAS overall scores of .73, p = .000. In North Carolina, there was also a significant correlation between ECERS-R and PAS overall scores of .69, p = .001. These correlations indicated that ratings of classroom environment quality were strongly associated with the quality of administrative practices in each system.

Discussion

The ECERS-R scores were significantly higher in programs from North Carolina than in programs from a mid-size city in Turkey. The high scores in North Carolina are consistent with previous studies conducted in the state and support the value of a well-developed QRIS based on clear standards, reliable monitoring, and intentional supports. In addition, the ECERS-R is used as an official assessment tool in the QRIS, providing early educators in these programs with access and training on the expectations of the tool prior to its administration.

The results of the study did not indicate significant differences between the PAS scores measuring the quality of administrative practices across the two systems. It was notable that, in both systems, the subscale scores were in the low to medium level. Overall, results from the study suggested that administrative practices play a critical role in supporting high-quality ECE programs, as indicated by the significant, positive correlation between the quality ratings of classroom environments and ratings of administrative quality in both Turkey and North Carolina.

Implications

In emerging quality improvement systems, such as in Turkey, there needs to be an emphasis on helping programs understand the standards for quality and ensuring that measurement systems are validated.

Results from this study suggest that it may be important for quality improvement systems in different cultural contexts to assess administrative practices as well as classroom quality.

Standards for administrative practices in different global contexts need to be established, and then measures such as the PAS should be included in the program quality evaluation system. The PAS was first developed, and most recently revised in 2022, to help program leaders in the United States incrementally improve program administrative quality by establishing clear benchmarks of quality associated with child care licensing standards (at the minimal level of quality), national program accreditation standards (at the good level of quality) and universal prekindergarten standards (at the excellent level of quality). Further research is needed to determine whether the PAS can reliably measure administrative quality in different cultural contexts.

Table 1

ECERS-R scores for Turkish and North Carolina Classrooms

References

- Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2005). Early Childhood Environment Scale–Revised. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Hujala, E., Eskelinen, M., Keskinen, S., Chen, C., Inoue, C., Matsumoto, M., & Kawase, M. (2016). Leadership tasks in early childhood education in Finland, Japan, and Singapore. Journal of Research in Childhood Education 30(3), 406-421.

- Kalkan, E., & Akman, B. (2010). The Turkish adaptation of the program administration scale. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 2060-2063.

- Li, J. (2015). What do we know about the implementation of the quality rating and improvement system? A cross-cultural comparison in three countries. Doctoral Dissertation. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

- Lower, J. K., & Cassidy, D. J. (2007). Child care work environments: The relationship with learning environments. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 22(2), 180-204.

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2010a, Winter). Head Start administrative practices, director qualifications, and links to classroom quality. Research Notes. Wheeling, IL: National Louis University.

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2010b, Summer). Connecting the dots: Director qualifications, instructional leadership practices, and learning environments in early childhood programs. Research Notes. Wheeling, IL: National Louis University.

- OECD. (2015). Strong start—IV: Improving monitoring policies and practice in early childhood education and care. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233515-en.

- Sheridan, S., Giota, J., Han, Y. M., & Kwon, J. Y. (2009). A cross-cultural study of preschool quality in South Korea and Sweden: ECERS evaluations. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(2), 142-156.

- Talan, T. N., Bella, J. M., & Bloom, P. J. (2022 in press). Program Administration Scale: Measuring whole leadership in early childhood centers. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Talan, T. N., & Bloom, P. J. (2004). Program Administration Scale: Measuring early childhood leadership and management. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Yaya-Bryson, D., Scott-Little, C., Akman, B., & Cassidy, D. (2020). A comparison of early childhood classroom environments and program administrative quality in Turkey and North Carolina. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52, 233-248.