BY McCormick Center | September 7, 2016

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

The upsurge in adding preK to elementary education has many principals and district leaders facing uncharted waters. School systems designed for traditional elementary education may not be a good fit for preK, especially for instructional leadership. Some concerns have been raised about whether principals are prepared to support and supervise preK teachers.1,2

The McCormick Center partnered with the National Association for Elementary School Principals (NAESP) and New America to explore instructional leadership in school-based preK classrooms across the U.S. NAESP members were surveyed about various aspects of instructional leadership in preK. This study expands our understanding of who is providing instructional leadership and how specific functions are distributed.

SAMPLE

An online survey—the National Principals’ Survey on Early Childhood Instructional Leadership3—was conducted in January 2016 with the NAESP membership. There were 459 principals who fully completed at least one section of the survey and of these, 321 (70%) reported they had an early learning program in their school. Respondents’ schools were located in 49 states or territories and the District of Columbia. Of the schools with preK, 67% offered preK up to middle school, 18% had preK and primary classrooms, and 15% were exclusively preK classrooms. The average preK enrollment of all the schools that offered early childhood education was 90 children.

Only one-fourth of the principals of schools with preK programs held early childhood certification. A majority of principals, however, had some coursework in early childhood education and had teaching experience in early childhood or elementary classrooms.

RESULTS

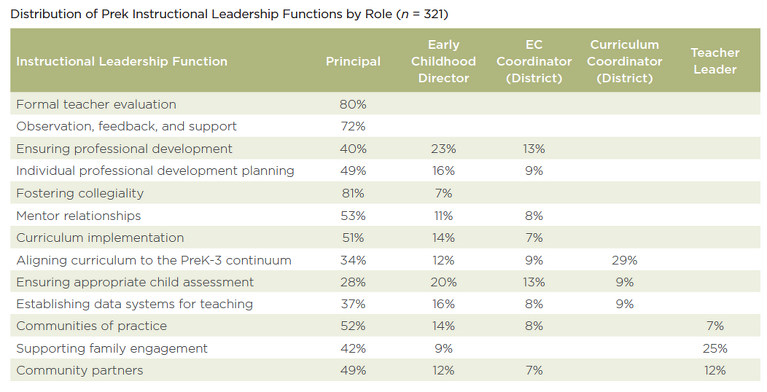

Most of the instructional leadership functions were primarily performed by individuals with five role titles—principal, early childhood director, early childhood coordinator at the district level, district curriculum coordinator, and teacher leader. The following table shows the percentage of schools in which the primary person responsible for various instructional leadership functions was identified with one of these five role titles.

The results of this study show that in most schools, principals considered themselves as the primary individual responsible for instructional leadership. In addition to principals, three of the role titles were reported to be the responsible in 20% or more of the schools. Early childhood directors were found to be the primary instructional leader for two functions: ensuring professional development and ensuring appropriate child assessment. Curriculum coordinators at the district-level were frequently identified as the person responsible for aligning curriculum to the PreK-3 continuum. Interestingly, in addition to principals, teacher leaders assumed key roles in supporting family engagement.

Limitations of this study should be considered in interpreting these results. Findings are based on self-reported information by principals and do not reflect the perspectives of other school personnel. While the respondents represented nearly all regions of the United States, the sample size was not robust enough to consider the findings representative of all principals or schools. Only NAESP members were surveyed, which does not include all elementary school principals. The respondents voluntarily participated yielding a disproportionate number of schools with preK classrooms.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

These findings help us understand how schools with preK programs are structured. Of the elementary schools that offer early childhood, about one-third are either schools operated by districts that are exclusively composed of preK classrooms or those that offer only primary grades—preK up to 3rd grade. The impact of different grade-level configurations warrants additional study, especially investigation of the effects of collectively educating young children in exclusively preK schools.

The finding of five primary instructional leadership roles is important as we seek to construct frameworks for distributed leadership in schools. The overwhelming prevalence of principals fulfilling most of the instructional leadership roles suggests that systems may not be in place to distribute leadership functions for greater organizational breadth. However, the emergence of the early childhood director as a chief leader in many school-based programs may indicate that administrators are beginning to recognize a need for specialized expertise in early childhood education and are taking steps to increase their school’s leadership capacity.

One example of this kind of response is the Midwest Expansion of the Child-Parent Center (CPC) Education Program in Illinois and Minnesota. Program partners developed a distributed leadership structure that involves a team of school personnel to support preK-3rd grade instruction. In addition to the principal and assistant principal, team members include: a curriculum liaison, a parent involvement liaison, a school-community representative, a parent resource teacher, and a head teacher. While many schools may not have the resources to support such a robust instructional leadership team, models such as those of the Midwest CPC Expansion project demonstrate greater leadership capacity to foster a constructivist leadership approach.4

Two of the five roles that emerged as primary instructional leaders were district-level positions—early childhood coordinator and curriculum coordinator. Many of the same instructional leadership functions that were performed by early childhood directors were also assigned to district early childhood coordinators. These district-level positions may fill key linchpin roles for schools, connecting schools across districts and fostering vertical collaboration along the PreK-3 continuum.

Teacher leaders were also identified as meeting the leadership needs in preK classrooms in many schools. Second only to principals, teacher leaders were most often considered the responsible party for supporting family engagement.

This exploratory study is a first step in understanding distributed leadership for schools with preK classrooms. More knowledge is needed about how to successfully frame the role of the principal in impacting preK pedagogy. It also reflects changes in the grade-level configuration of schools, and documents the prevalence of schools that are exclusively early childhood programs across the United States. The findings of this study challenge existing norms for principal preparation and underscore the importance that all instructional leaders of preK classrooms have the specialized knowledge to support exemplary pedagogical practices for young learners.

- Shue, P. L., Shore, R. A., & Lambert, R. G. (2012). Prekindergarten in public schools: An examination of elementary school principals’ perceptions, needs, and confidence levels in North Carolina. Leadership and Policy in Schools 11, 216–233. DOI: 10.1080/15700763.2011.629074

- Sokoloff-Rubin, E. (2014, August 26). Are principals prepared to evaluate pre-K teachers? Chalkbeat. (Online Magazine). Retrieved from: http://ny.chalkbeat.org/ 2014/08/26/are-principals-prepared-to-evaluate-pre-k-teachers/#

- Abel, M. B., Talan, T. N., Pollitt, K. D., & Bornfreund, L. (2016, July). National principals’ survey on early childhood instructional leadership. Wheeling, IL: McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University. http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/mccormickcenter-pubs/1

- Lambert, L., Zimmerman, D. P., & Gardner, M. E. (2016). Liberating leadership capacity: Pathways to educational wisdom. New York: Teachers College Press