BY McCormick Center | May 7, 2018

Sim Loh is a family partnership coordinator at Children’s Village, a nationally-accredited Keystone 4 STARS early learning and school-age enrichment program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, serving about 350 children. She supports children and families, including non-English speaking families of immigrant status, by ensuring equitable access to education, health, employment, and legal information and resources on a day-to-day basis. She is a member of the Children First Racial Equity Early Childhood Education Provider Council, a community member representative of Philadelphia School District Multilingual Advisory Council, and a board member of Historic Philadelphia.

Sim explains, “I ensure families know their rights and educate them on ways to speak up for themselves and request for interpretation/translation services. I share families’ stories and experiences with legislators and decision-makers so that their needs are understood. Attending Leadership Connections will help me strengthen and grow my skills in all domains by interacting with and hearing from experienced leaders in different positions. With newly acquired skills, I seek to learn about the systems level while paying close attention to the accessibility and barriers of different systems and resources and their impacts on young children and their families.”

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

In response to the 2017 release of NAEYC’s Early Childhood Higher Education (ECHE) Directory,1 Mary Harril, Senior Director of Higher Education at the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), raised some important concerns about the complexity of degree programs and pathways for the early childhood education workforce.2 She noted that there are over 3,000 early childhood degree programs, with more than 60 different names at certain levels, which may include multiple tracks for each degree, and are housed in a variety of divisions or departments within a college or university. Researchers at the McCormick Center examined the ECHE Directory to determine the prevalence of degree programs for early childhood leaders and posted the results on the L.E.A.D. Early Childhood Clearinghouse website.3 They found a similar array of degree names and complexity in the education pathways to program leadership, which suggests a need to define and clarify how ECE leaders—directors, family child care providers, and other administrators—are prepared. As NAEYC facilitates the Power to the Profession initiative, specialization in early childhood program leadership is especially relevant. Greater clarity about the professional preparation of the early childhood workforce, including program leaders, is needed as the Power to the Profession initiative advances. This study is particularly useful in identifying post-secondary education programs that prepare and support early childhood leaders.

METHODS

In the fall of 2016, McCormick Center staff scanned the NAEYC ECHE Directory and identified programs that included early childhood leadership, management, administration, or advocacy in the degree program’s name. It was evident that many degree programs offer coursework in leadership and management; however, for the purposes of this study, it was assumed that if it was not referenced in the degree’s name, it was not the primary focus of the course of study. Then researchers conducted further analysis of the identified programs by examining content on each individual program’s website to verify its focus and to collect additional information. A comprehensive dataset was created that contained the number of institutions, number of programs, type of institution (public or private), duration of the degree programs (2-year or 4-year), degree levels, and learning modalities (in-person, on-line, or blended).

The higher education data were included in the creation of profiles for all 50 states and the District of Columbia on the L.E.A.D. Early Childhood Clearinghouse website. They were also combined as part of a national profile on the status of early childhood program leadership. In June 2017, NAEYC revised the ECHE Directory. McCormick Center staff reviewed the revised site and updated the dataset and information on the L.E.A.D. Early Childhood Clearinghouse website.

FINDINGS

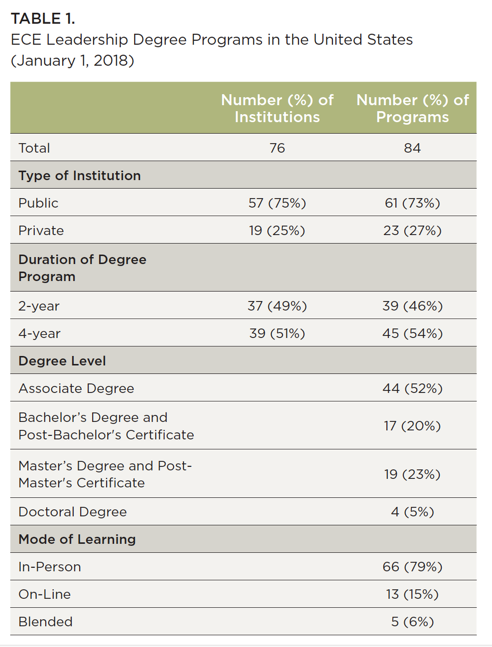

The researchers found 84 higher education degree programs (3% of total ECE programs), at 76 college and university campuses in the United States, with a specific focus on early childhood leadership, management, administration, or advocacy. They were located in 34 states and the District of Columbia. Table 1 shows statistics from the national scan.

A majority of early childhood leadership degree programs (73%) are offered at public institutions and 27% at private colleges and universities. Leadership degrees are offered at both 2-year institutions (46%) and 4-year institutions (54%).

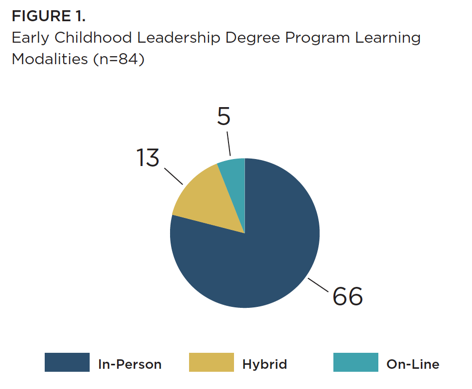

It is possible to find post-secondary education in early childhood leadership at all degree levels. Over half of the programs (52%) confer Associate degrees, with 20% and 23% at the Bachelor’s degree and Master’s degree levels respectively. There are four doctoral programs (5%) in early childhood leadership in the United States. Most programs (79%) are delivered in-person; however, 15% are offered exclusively on-line and 6% are hybrid programs. Figure 1 shows the number of programs by learning modality.

This study revealed that access is uneven to higher education offerings in early childhood leadership. While programs are available in only 34 states, 13 programs are offered entirely online. Coursework is available for students at multiple levels—associate through doctoral degrees. Geographic presentation of the programs, and links to their websites, is available through maps on the L.E.A.D. Early Childhood Clearinghouse website.

DISCUSSION

The McCormick Center researchers were surprised to learn of 84 early childhood degree programs in early childhood leadership. A comprehensive study of higher education programs with this specialization had not previously been conducted and the substantial number of ECE leadership degree programs was greater than expected. The findings of this study suggest a rapid growth of leadership as an academic discipline in recent decades.

Some of the concerns that Mary Harrill raised in the New America blog also apply to leadership programs in higher education. The naming of degrees is not standardized making it difficult to compare across programs. By examining each individual program’s website, McCormick Center researchers were able to examine how these programs emphasized leadership, management, administration, and/or advocacy. The emergence of early childhood leadership as an academic discipline raises some important questions and considerations for the field, especially during this time of professionalization of the early childhood workforce. One question raised by the Power to the Profession initiative is whether early childhood program leaders—directors, family child care providers, and other administrators—are part of the early childhood education profession. The answer to this question has significant implications for the content of higher education programs designed to prepare program leaders. Additional research is needed about the early childhood leadership workforce and the preparation of individuals pursuing both pedagogical and administrative leadership roles.4 More information about the nature of leadership preparation degree programs would help guide this emerging specialization.

REFERENCES

- NAEYC Early Childhood Higher Education Directory. https://degreefinder.naeyc.org/

- Harril, M. (December 1, 2017). Tomayto, Tomahto: What’s in a [Degree] Name? Blogpost. New America: https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/tomayto-tomahto-whats-degree-name/

- Closing the Early Childhood Leadership Gap. (January 1, 2018). McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership: http://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/lead/closing-the-leadership-gap/

- Abel, M. B., Talan, T. N., & Masterson, M. (2017, Jan/Feb). Whole leadership: A framework for early childhood programs. Exchange (19460406), 39(233), 22-25.