BY McCormick Center | September 3, 2015

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

While there is considerable research about the nature and practice of leadership in business, K-12 education, and health sciences, evidence regarding early childhood leadership is relatively thin. Some research regarding early learning programs is available about organizational climate,1 change management,2 administrative best practice,3 and the influence of the administrator.4 International studies, as well, have added to our understanding of what early childhood leaders need to know and be able to do.5, 6

One way to conceptualize early childhood leadership is to consider two functional types—administrative leadership and instructional (or pedagogical) leadership. Administrative leadership involves creating management systems to leverage resources, oversee operations, and engage stakeholders. Instructional leadership inspires effective teaching and learning within a culture of continuous quality improvement. It focuses on creating a positive work climate, ensuring the organizational conditions that foster professional growth and effective teaching. A recent study in Victoria, Australia provides an interesting perspective when considering these two leadership functions.7

SAMPLE AND METHODS

The goal of the Australian study was to examine perceptions of important leadership capacities of 351 individuals selected to participate in a 4-month leadership development program between 2010 and 2013. The training included face-to-face learning days, cohort meetings, mentoring, and an inquiry-based project in their workplace. Participants were selected for the leadership training if they were early childhood professionals responsible for leading a team or managing a program. A distribution of various program types was represented in the sample including community, private, and government entities. Most of the participants were program directors, but some were director/teachers. A smaller percentage had primary responsibilities related to early intervention. Over two-thirds of the participants had earned a college degree and a majority had five or more years’ experience in the field.

Participants responded to an online questionnaire at the beginning of the training course to explore their perceptions about early childhood leadership. They were asked: What do you think are the most important things an early childhood leader should have the capacity to do? A 4-point scale was used: 1 = not important, 2 = not very important, 3 = fairly important, and 4 = very important.

RESULTS

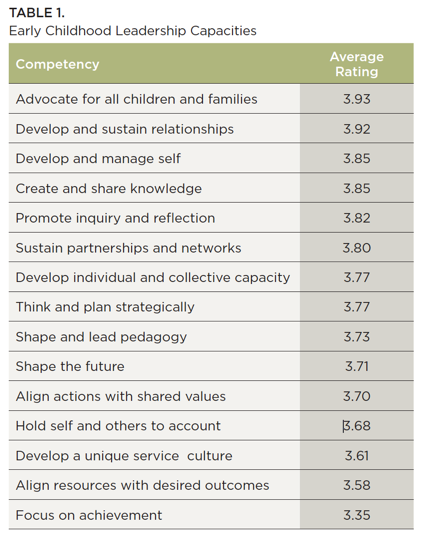

Results showed that on average participants rated all 15 of the capacities as important (3.0 or above), which was expected because the questionnaire was based on the training program’s leadership framework. Table 1 shows the perceived importance of early childhood leadership capacities listed in rank order based on participants’ average ratings.

Advocating for children and families was highly rated; yet additional data collected in the study showed that this value was not reflected in participants’ practice. Respondents ranked leadership capabilities related to personal characteristics and relationship building (e.g., self-regulation; developing and sustaining relationships; and sustaining partnerships) as very important. Collectively, items related to instructional leadership (e.g., developing individual and collective capacity; shaping and leading pedagogy; promoting inquiry and reflection; and creating and sharing knowledge) were ranked lower than advocacy or relationship building. Capacities related to administrative leadership (e.g., aligning resources with outcomes; developing a unique service culture; thinking and planning strategically) ranked lowest in the list.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

This study raises awareness that early childhood program leaders in Australia do not perceive key aspects of instructional leadership as most critical to their work and program administration is less important than personal and social capacity. Leaders in this study believe they must primarily be able to self-regulate and motivate others. Through these leadership capacities they are able to build the collective competence of learning organizations to create knowledge, promote inquiry and reflection, and align behaviors around shared values. They perceive relationship building as central to the role of the leader and a key lever to success in early learning. This research affirms values that “people skills” are necessary for advancing organizations to help children succeed in school and in life. Less emphasis is placed on leadership knowledge and skills that focus on program quality outcomes.

In the United States, the director’s role is more likely to be conceived as pedagogical leader, vision builder, talent developer, data manager, knowledge broker, and systems engineer.8 These capacities are directly related to leading others for program effectiveness of learning organizations. The focus is still about helping children succeed, but the leader’s role is perceived somewhat differently from that of the Australian study participants.

A caution—the contextual environment and workforce systems must be considered when making conclusions about various approaches to leadership development. Certainly there are differences in early childhood education between Australia and the United States, but exploring new perspectives about the role and capacities of leaders may be beneficial.

- Bloom, P. J. (2010). Measuring work attitudes in the early childhood setting (2nd ed.). Wheeling, IL: McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Bloom, P. J., Jackson, S., Talan, T. N., & Kelton, R. (2013). Taking Charge of Change: A 20-year review of empowering early childhood administrators through leadership training. Wheeling, IL: McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Talan, T. N. & Bloom, P. J. (2011). Program Administration Scale: Measuring early childhood leadership and management (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Bloom, P. J. & Abel, M. B. (2015). Expanding the lens—leadership as an organizational asset. Young Children, 70(2), 10-17.

- Davis, G. (2012). A documentary analysis of the use of leadership and change theory in changing practice in early years settings. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 32(3), 266-276. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2011.638278

- Ressler, G., Doherty, G., McCormick Ferguson, T., & Lomotey, J. (2015). Enhancing professionalism and quality through director training and collegial mentoring. Canadian Children, 40(1), 55-72.

- Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2015). Conceptions of early childhood leadership: Driving new professionalism? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(2), 149-166. doi:10.1080/13603124.2014.962101

- Bloom, P. J., Hentschel, A., & Bella, J. (2013). Inspiring peak performance: Competence, commitment, and collaboration. Lake Forest, IL: New Horizons.