BY Robyn Kelton, MA, and Irina Tenis, PhD | June 21, 2024

Meeting the Needs of the Proficient Early Childhood Administrator

by Robyn Kelton, MA, and Irina Tenis, PhD

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

INTRODUCTION

Research has established the vital role administrators play in the success and sustainability of high- quality early childhood care and education (ECEC) programs (Doherty et al., 2015; Lower & Cassidy 2007; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2010, 2022; Rohacek, et al., 2010). However, many center-based program administrators assume their leadership roles by being promoted from a teaching position (Abel et al., 2018; Douglass, 2019; Kirby et al., 2023; Kelton & Talan, 2023; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018). Consequently, while they may assume their administrative role with a strong background in teaching young children, they often lack the specific education, specialized training, and experience needed to successfully lead and sustain a high-quality ECEC program (Abel et al., 2018; Bloom et al., 2013; Kelton & Talan, 2023; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018; Talan et al., 2014). In fact, a recent study found that 71% of program administrators reported feeling unprepared for the issues they faced (Kelton & Talan, 2023).

Adult learning theory, as well as research across many workforce sectors, including early childhood education (e.g., Raduan & Na, 2020; Dall’Alba & Sandberg 2006; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986; Fukkink & Lont, 2007; Kinchin & Cabot, 2010) highlights the need to align professional development opportunities with career development stages. In 1997, Paula Jorde Bloom created The Directors’ Role Perceptions Survey (DRPS) to examine the perceived roles and work history of 257 center administrators (Rafanello & Bloom, 1997; Bella et al., 2017). For nearly 30 years, the DRPS and, more recently, the Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS) have used self-perceptions of mastery of key early childhood program leadership competencies, rather than years of experience to categorize ECEC center-based administrators into three distinct career development stages—novice, proficient or capable, and advanced or master (Abel et al., 2019; Bloom, 2007, 2019; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018; Rafanello & Bloom, 1997).

Predictably, specific differences in the training and coaching needs of administrators for each stage have emerged in the literature (e.g., Bloom & Bella, 2005; Bloom et al., 2013; Kelton & Talan, 2023; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018). Further research has shown that professional development, tailored to the needs of administrators at different career stages, leads to individual improvement in self-efficacy and mastery of leadership competencies as well as organizational gains in program quality and organizational climate (e.g., Bloom et al., 2013; Doherty, 2015; Kelton & Talan, 2023; Talan et al., 2014). This highlights the importance of considering career development stages when designing and delivering professional learning opportunities for administrators. Yet, many professional learning experiences for administrators are broadly approached with a one-size-fits-all mentality, placing little emphasis on the different competencies, experiences, and needs of administrators at various career stages.

As Douglass & Kirby noted, “ECE leadership development and practice needs more empirical evidence to inform the supports and systems that are necessary to strengthen leadership at all stages of its development” (2022, p. 11). While McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership’s work (2018) provided broad profiles of administrators’ role perceptions and self-identified professional development needs by career development stage, this Research Brief aims to expand on that work by providing an in- depth profile of the largest career development stage group: the proficient administrator. Building on the established characterization of proficient administrators as those who shift from struggling to juggling responsibilities, focus on improving their efficiency and effectiveness, and fit into the conscious competence learning stage (Bloom, 2007, 2019), this study examines their perceived alignment between current and ideal work experiences, career origins, current role perceptions, levels of self-efficacy, and mastery of critical leadership competencies.

METHOD

This study included 103 center-based administrators whose ARPS profile scores identified them as in the proficient career development stage. The ARPS is a self-report measure completed by early childhood program administrators to measure perceptions about their roles, leadership competency, and professional development needs aligned with the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership’s Whole Leadership Framework (Abel et al., 2019; Bella et al., 2017). The sample included ECEC administrators from nine US states (KS, IL, IN, MI, MN, NJ, OK, TX, & WA). The majority (61%) of the sample identified their current role title as director, 15% as assistant director, 13% as owner-director, and 12% as executive director. Seventy-two percent indicated that they shared their administrative responsibilities with at least one other person, and 20% indicated that their job description included regularly assigned classroom teaching.

The majority (62%) of the sample identified as White or Caucasian, 15% as Hispanic/Latinx, 11% Black or African American, 5% Asian, 4% as Multiracial, 2% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 2% selected other. The sample predominantly identified as female (94%); 6% identified as male.

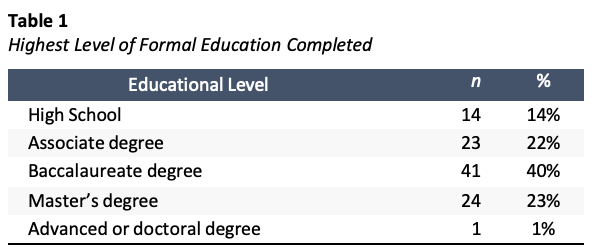

The majority (86%) of the sample reported having earned a college degree. See Table 1 for a detailed breakdown. Of 89 respondents who reported having earned a college degree, 65% majored in child development or early childhood education. Thirty-three percent of the sample had an early childhood teaching license, and 14% had an elementary teaching license. Comparatively, only 28% of the sample had a state or national administrator or director credential, and 4% had a principal endorsement. Eleven percent reported having previously participated in an early childhood leadership academy.

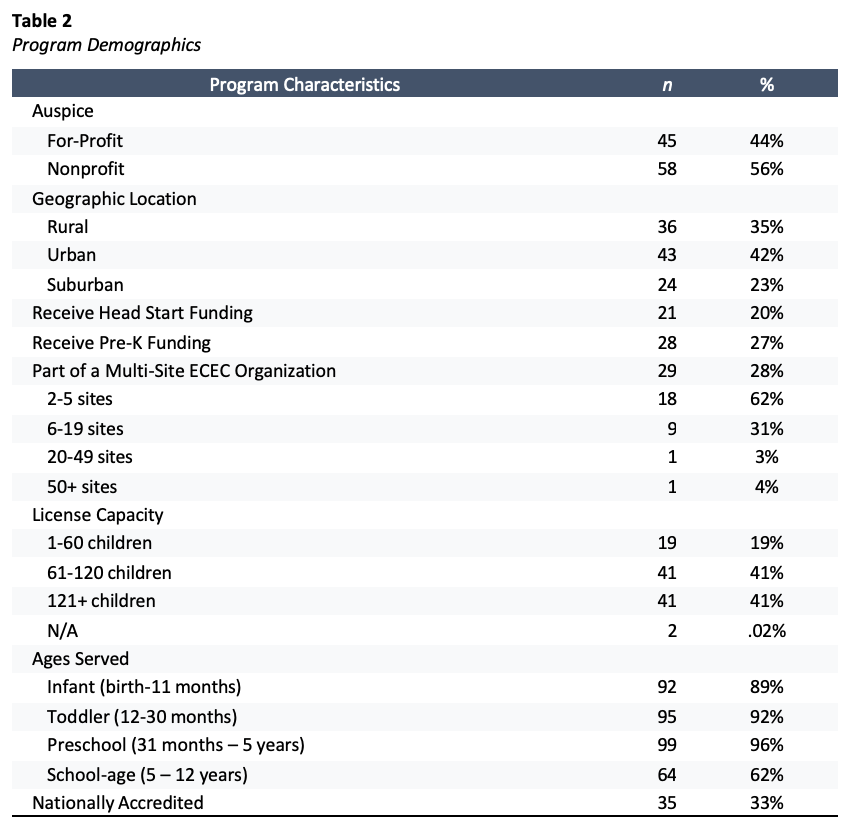

Respondents reported having worked in the ECEC field between three and 45 years with an average of 18 years. Years of experience in an administrative role ranged from less than one to 37 with an average of ten years. Years of experience in their current administrative role ranged from less than one to 37 with an average of seven. The 103 administrators represented ECEC programs that varied in size, ages served, legal auspice, and funding. Table 2 provides details on program demographics.

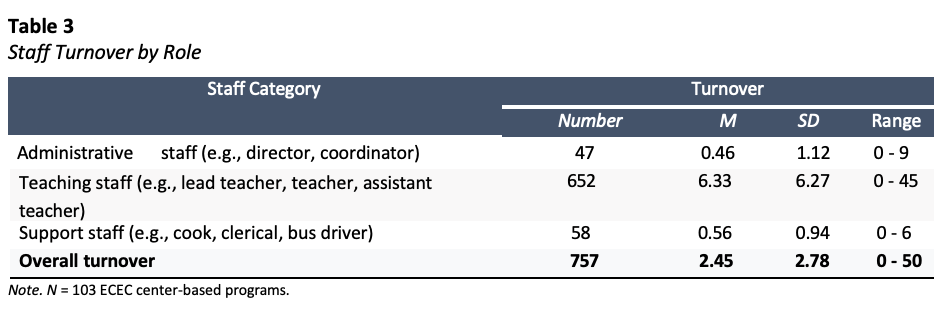

Nearly all of the sample (95%) reported staffing turnover had occurred in their program within the past 12 months. Of the 103 programs represented, 97 programs (94%) had at least one teaching staff member leave their program within the past twelve months, 29% of programs had administrator turnover, and 39% had support staff turnover. Table 3 provides the statistics of staff turnover by role across all 103 programs.

Measures

The Administrator Role Perception Survey (ARPS) was used to collect data for this study between 2022 and 2024. The ARPS examines role perception, commitment, job satisfaction, and identifies administrators’ developmental career stages based on their perceptions of mastery of key early childhood program leadership competencies (Abel et al., 2019; Bella et al., 2017). The ARPS also provides information regarding administrators’ internalized practices, levels of self-efficacy, and competencies in 36 areas across the three Whole Leadership domains: leadership essentials, administrative leadership, and pedagogical leadership. The survey is administered online, takes about 25-minutes to complete, and consists of 48 items regarding role perceptions and self-efficacy, 14 demographic items, and 7 items about program characteristics. Higher scores on the leadership self- efficacy subscales indicate higher levels of confidence in perceived leadership competence. The ARPS is able to categorize administrators as novice, proficient, or advanced based on self-identified levels of self-efficacy and competence across key leadership functions (Abel et al., 2019; McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, 2018).

FINDINGS

Career Beginnings

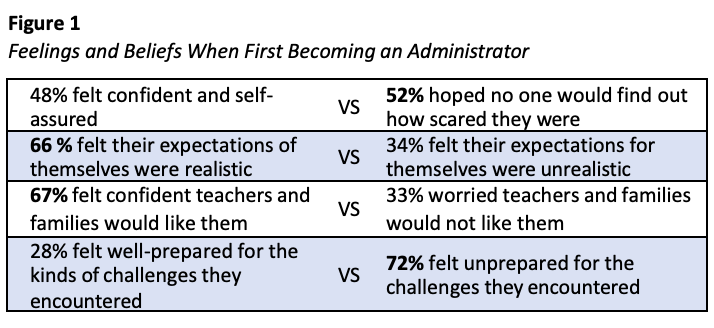

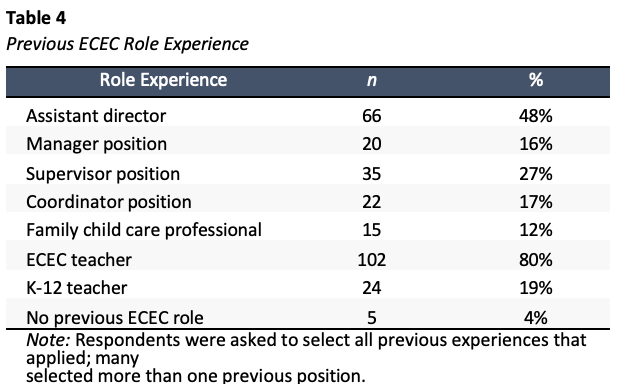

While most proficient administrators reported that when first assuming their administrative role, they felt confident that they would be liked and that they had realistic expectations for themselves, they also reported being unprepared and scared. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of responses. Proficient administrators were also asked about their previous ECEC experience. On average, respondents had held two previous ECEC-related roles. The vast majority (80%) had previous ECEC teaching experience, and 65% of proficient administrators held at least one previous supervisory or managerial role. Table 4 below provides a breakdown of previous ECEC role experience.

Current Role Perception, Job Satisfaction, and Confidence

Role Perception

Respondents were asked to select the three words or phrases that best described their role. Based on frequency, the top three choices for proficient administrators were leader (48%), problem solver (48%), and decision maker (38%). Proficient administrators also tend to describe their job as rewarding (47%), yet challenging (47%) and demanding (39%).

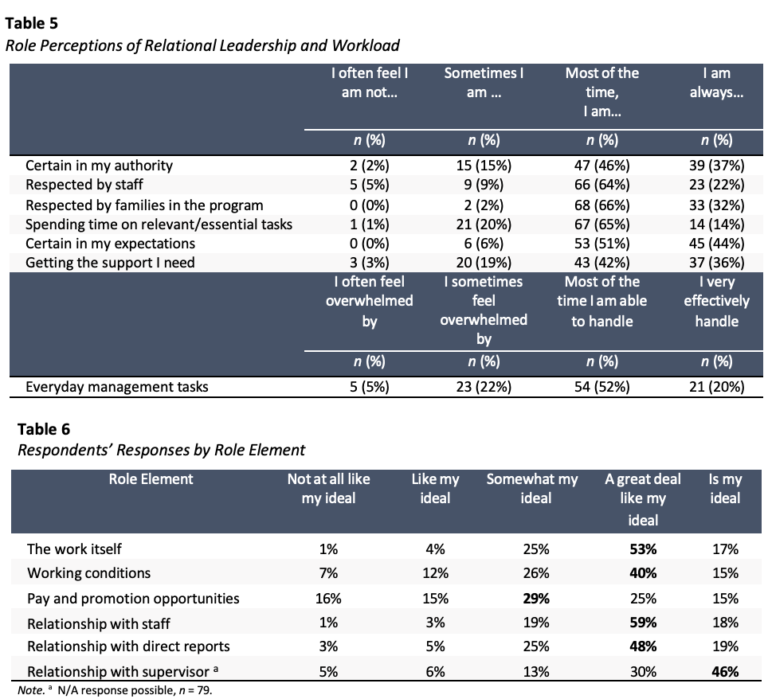

Respondents were also asked to respond to seven Likert-type items about how they perceived aspects of their relational leadership and their workload as an administrator. Table 5 summarizes the responses for each question regarding the respondent’s perceptions, with 1 being the most negative answer (e.g., “I am often uncertain about how much authority I have”) and 4 being the most positive answer (e.g., “I always know how much authority I have”).

Job Satisfaction

Respondents were asked to rate, on a Likert-scale, how well specific elements of their work aligned with their ideals (0 = not at all like my ideal, to 5 = is my ideal). Table 6 shows the alignment percentages by element.

The ARPS also asked administrators to describe the aspects of their work that brought them the greatest sense of satisfaction and greatest frustration. For proficient administrators, a significant source of frustration was staffing issues, including difficulty finding and retaining qualified staff, staff turnover, lack of work ethic or professionalism, and staff conflicts or gossip. Time management was also frequently noted as a source of frustration, with proficient administrators struggling to complete tasks and balance responsibilities. Other frustrations included lack of support or resources, navigating rules and regulations, dealing with difficult families, and feeling a lack of autonomy or control. Some also expressed frustration with the low pay and lack of respect for the field. Despite the challenges, proficient administrators appeared to take pride in their work and the connections they form. Common areas of satisfaction included seeing children grow and learn, building positive relationships with staff and families, and making a meaningful impact.

Confidence in Leadership Functions

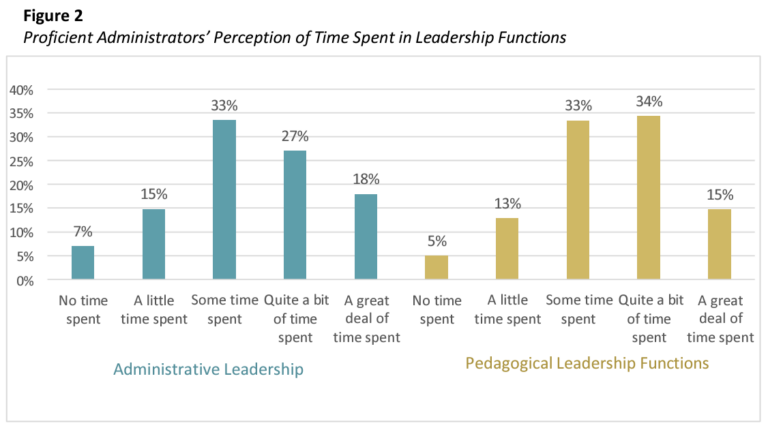

Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of time they spend on administrative leadership and pedagogical leadership functions based on 24 domain specific functions using a 5-point Likert scale, from “1 = No time spent” to “5 = A great deal of time spent”. Figure 2 below depicts the perceived distribution of time spent focused on administrative and pedagogical leadership.

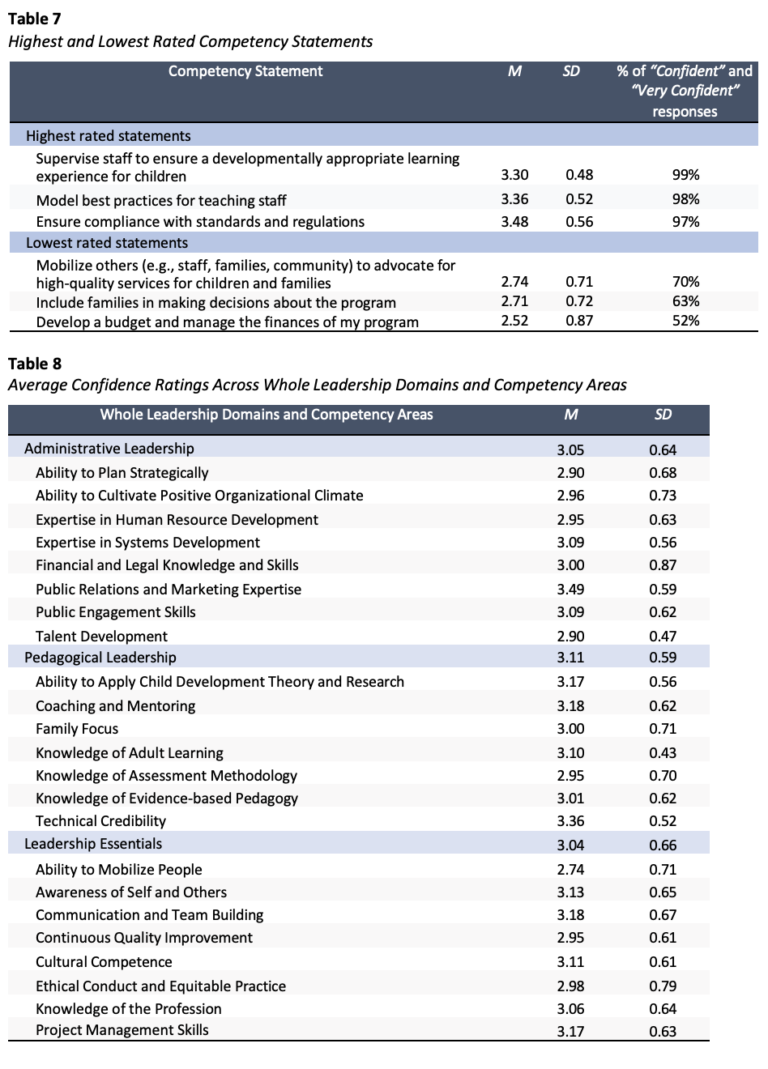

Respondents also rated their confidence on each of the 36 competency statements in the ARPS using a 4-point Likert scale (“1 = I am not confident in my ability to…” to “4 = I am very confident in my ability to…”). The statements where respondents felt most confident and least confident are provided in Table 7.

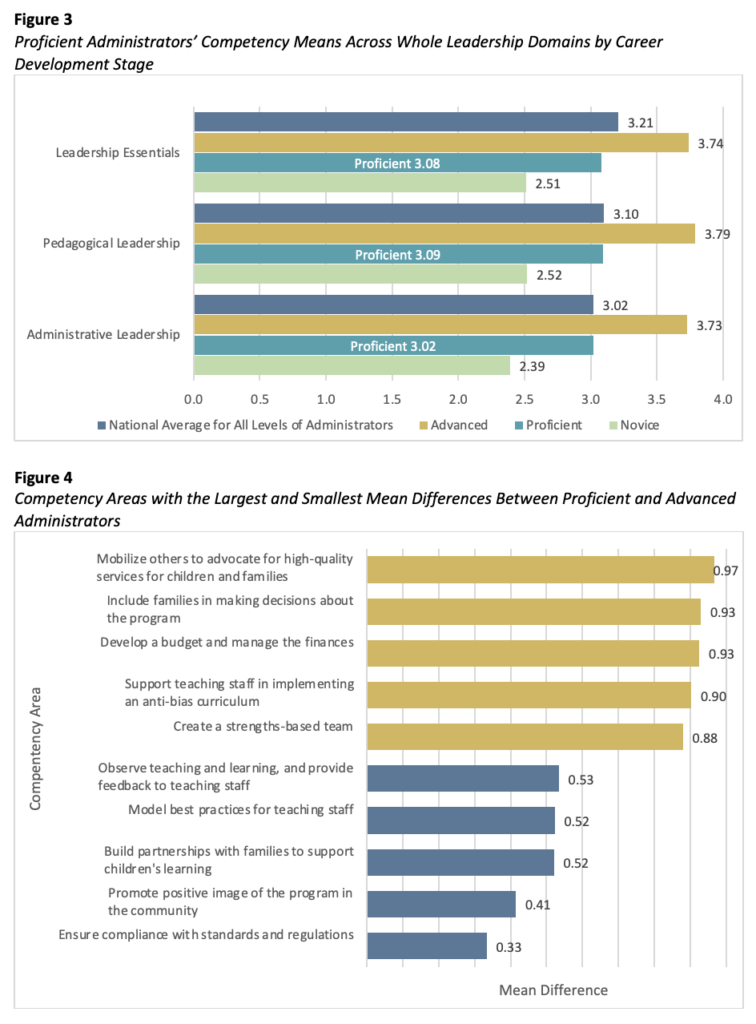

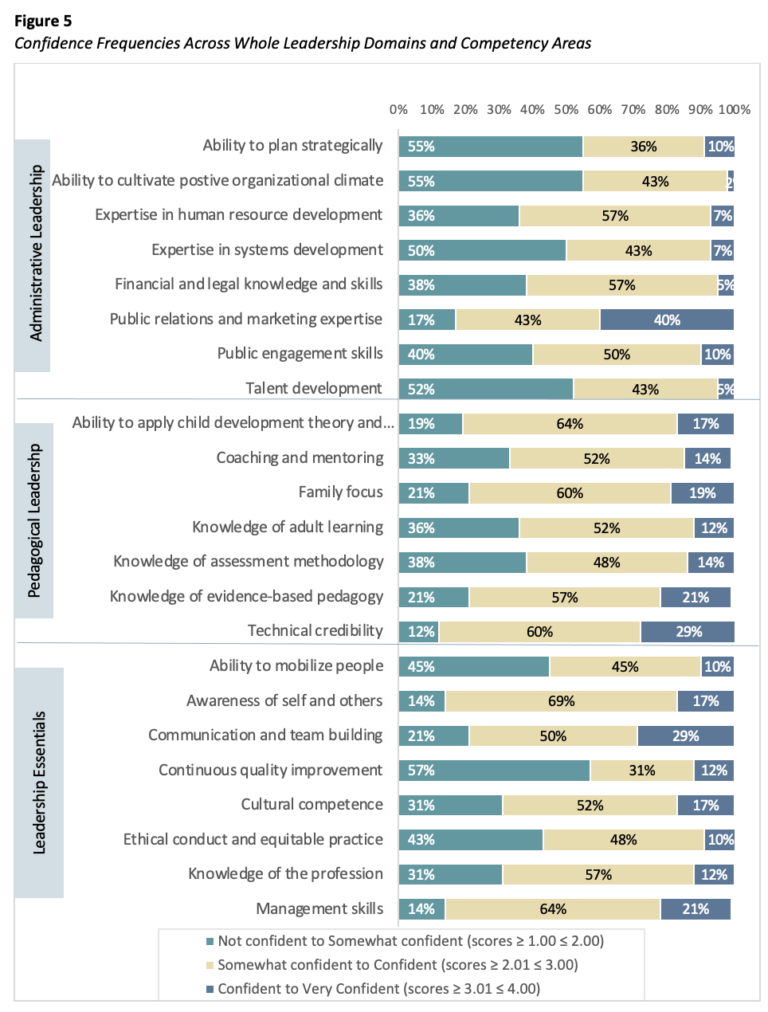

Confidence ratings across the three Whole Leadership domains were calculated based on the responses to 36 competency statements in the ARPS that captured competency areas within 23 areas across administrative leadership, pedagogical leadership, and leadership essentials. Table 8 provides mean ratings and standard deviations for each domain as well as competency across specific areas within each domain. For added perspective, Figure 3 demonstrates how means across the three domains of Whole Leadership differ by career stage. Figure 4 shows the five areas with the largest mean difference between proficient and advanced administrators, followed by the five areas with the smallest mean difference between the groups.

Last, Figure 5 provides a visual spread of the percent of proficient leaders who rated themselves as not confident or somewhat confident, somewhat confident to confident, and confident to very confident across competency areas within each Whole Leadership domain.

Commitment

Our sample of proficient directors appeared to be strongly committed to their role and dedicated to their work with 96% of proficient directors reporting that they intend to work as an administrator for at least three more years. However, when examining specific components of their current position and commitment to their organization, the data is more complex. Seventy-nine percent of respondents reported feeling very committed to their current organization, 80% reported taking pride in their organization, and 71% indicated that they put in a lot of extra time at work. And yet, 40% reported that they did not intend to work at their current organization for at least two more years, 11% percent expressed that they often think of quitting, and 67% did not feel it would be difficult to find another job as good as their current one.

DISCUSSION

Early childhood program leadership is crucial for ensuring high-quality education, supporting teacher development, promoting child development, engaging families, maintaining safety, driving innovation, and achieving overall program success. Effective administrators create nurturing, efficient, and forward- thinking environments that lay a strong foundation for children’s future learning and development.

Research and theory in adult learning provide a robust foundation of theoretical and empirical support for the alignment of professional development with career development stages. Such alignment for ECEC administrators suggests that professional development targeted for specific career development stages leads to effective learning experiences, greater employee satisfaction, and enhanced organizational performance. Kelton and Talan (2023), for example, found that participation in an intensive leadership academy created to meet the specific needs of new directors (those in their first 5 years of an administrative role) resulted in statistically significant gains in a number of specific leadership competencies and across all three of the Whole Leadership Framework domains: administrative leadership, pedagogical leadership, and leadership essentials. Similarly, researchers examined outcomes over 20 years of Taking Charge of Change, an intensive 10-month leadership academy targeting more seasoned directors in Illinois, and found statistically significant increases on three items in the Program Administration Scale (PAS): staff orientation, staff development, and family communication. Organizational climate, as measured by program staff responses to the Early Childhood Work Environment Survey, also showed gains with statistically significant increases in the domains of decision making, goal consensus, innovation, and overall organizational climate (Bloom et al., 2013, Talan et al, 2014).

Yet, little is published regarding the developmental career stages of ECEC administrators. Expanding on the narrative work of Bloom and previous research by the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, this Research Brief provides a detailed profile of the proficient administrator.

Findings reveal a nuanced picture of proficient administrators’ initial experiences in their roles. While a substantial proportion (48%) felt confident and self-assured when first stepping into their administrative positions, an equally significant number (52%) harbored fears of being unprepared and scared. These data indicate that although many administrators believed their expectations were realistic (66%) and felt confident they would be liked by teachers and families (67%), a considerable majority (72%) felt unprepared for the challenges they encountered. This dichotomy suggests a need for more comprehensive preparatory programs that address the practical challenges administrators face early in their careers.

The majority of proficient administrators have teaching and some leadership experience, as well as a college degree. However, less than a third (28%) have an administrator credential, and only 11% report having completed a leadership academy. This background experience seems to provide a foundation, albeit insufficient, for the complex demands of leadership.

In their current roles, proficient administrators identified themselves primarily as leaders, problem solvers, and decision makers. Despite finding their roles rewarding (47%), they also described them as challenging (47%) and demanding (39%). This complexity in role perception underscores the multifaceted nature of administrative positions in ECEC settings. The survey data on role perceptions highlight that while most administrators felt respected by both staff (86%) and families (98%), a significant portion still experienced uncertainty about their authority (17%) and struggled with feeling overwhelmed by everyday management tasks (27%). These findings point to areas where targeted support and training could help alleviate stress and enhance role clarity and effectiveness.

Job satisfaction among proficient administrators appears to be influenced by several factors, including relationships with staff and supervisors, which were rated highly in terms of alignment with their ideals. However, elements such as pay and promotion opportunities were less satisfactory, with only 15% rating these aspects as ideal. This dissatisfaction with compensation and career advancement opportunities is a critical area for policy intervention as it impacts retention and overall job satisfaction.

With regards to levels of self-efficacy and perceptions of mastery of critical leadership competencies, the proficient administrator appears strongest in the Whole Leadership domain of pedagogical leadership. Across individual competency areas, proficient administrators felt strongest in: public relations and marketing expertise, coaching and mentoring, and communication and team building. Conversely, areas to highlight for improvement include the ability to mobilize staff, the ability to plan strategically, assessment methodology, and continuous quality improvement practices.

These findings highlight potential areas for targeted professional development that could aim to scale-up strengths where proficient administrators are moderately confident, such as knowledge of the ECEC profession or adult learning theory, as well as areas in which proficient administrators struggle, such as developing a budget. These data also point to some nuanced findings within Whole Leadership domains. For example, professional development regarding family engagement may want to focus more on gaining knowledge and skills that support collaborative decision-making processes and practices with families while spending less time on developing family partnerships to support children’s learning.

Despite the challenges, proficient administrators showed a strong commitment to their roles, with 96% intending to continue in their administrative capacity for at least three more years. However, commitment to their current organizations was less stable, with 40% not intending to remain with their current employer for two more years and 67% believing they could find an equivalent job elsewhere. These findings suggest that while administrators are dedicated to their profession, organizational factors such as financial support, professional resources, and career advancement opportunities play a crucial role in their long-term retention.

In summary, this research underscores the complexity and multifaceted nature of proficient administrators’ experiences in program leadership. The findings point to significant areas for support and development, particularly in financial management, strategic planning, and advocacy skills, while also highlighting the importance of addressing compensation and organizational support to enhance job satisfaction and commitment.

While limited in sample size, this study reaffirms the original description of the proficient administrator while providing critical details that can aid in the design and delivery of targeted professional development efforts to assist the proficient administrator progress to the advanced career development stage. As Bloom and Bella noted, career development progression from novice to proficient, and then to advanced, represents a transformation that is more multifaceted than the accumulation of new knowledge (2005). Therefore, future research and professional development opportunities for program administrators should consider Whole Leadership domains competencies, the relationship between Whole Leadership domains and competencies, efforts to increase self-efficacy as the fuel for leadership development, and the critical alignment of leadership development to career development stages.

REFERENCES

- Abel, M., Bella, J., Talen, T., & Magid, M. (2019). Administrators Role Perceptions Survey validation study: Technical report. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, August 2019

- Abel, M. B., Talan, T. N., & Magid, M. (2018). Closing the leadership gap: 2017 status report on early childhood program leadership in the United States. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Bella, J., Abel, M., Bloom, P.J., & Talan, T. (2017). Administrator Role Perception Survey. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Bloom, P.J. (2007). From the inside out: The power of reflection and self-awareness. New Horizons.

- Bloom, P., J. (2019). Director’s developmental Stages. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Bloom, P. J., & Bella, J. (2005). Investment in leadership training: The payoff for early childhood education. Young Children, 60(1), 32–40

- Bloom, P. J., Jackson, S., Talan, T. N., & Kelton, R. (2013). Taking Charge of Change: A 20-year review of empowering early childhood administrators through leadership training. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Dall’Alba, G., & Sandberg, J. (2006). Unveiling professional development: A Critical review of stage models. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 383-412

- Doherty, G., Ferguson, T. M., Ressler, G., & Lomotey, J. (2015). Enhancing child care quality by director training and collegial mentoring. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 17(1).

- Douglass, A. (2019). Leadership for quality early childhood education and care. OECD Education Working Papers, N 211. OECD Publishing.

- Douglass, A. &. Kirby, G. (2022). Evaluating leadership development in early care and education. OPRE Brief #2022-141. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Dreyfus H., L. & Dreyfus S., E. (1986) Mind over machine: The power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. New York Free Press.

- Ehrlich, S. B., Pacchiano, D., Stein, A.G., & Wagner, M.R. (2018). Early education essentials: Validation of surveys measuring early education organizational conditions. Early Education and Development, 30(2), 1-28.

- Fukkink, R. & Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 22. 294-311.

- Kelton, R., & Talan, T. N. (2023). We can’t afford to lose leaders: Professional development to increase administrator retention during the first few years. Research Notes. McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Kinchin, I., M., & Cabot, L., B. (2010). Reconsidering the dimensions of expertise: from linear stages towards dual processing. London Review of Education, 8(2), 153 – 166.

- Kirby, G., Douglass, A., & Malone, L. (2023). Understanding and measuring leadership in center-based early care and education to inform policy and practice. OPRE Brief, #2023-177. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Lower, J.K., & Cassidy, D., J. (2007). Child care work environments: The relationship with learning environments. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 22(2), 189−204.

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2010). Connecting the dots: Director qualifications, instructional leadership practices, and learning environments in early childhood program. Research Notes. National Louis University.

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2018). Director’s professional development needs differ by developmental stage. Research Notes. National Louis University

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2019). Whole Leadership framework for early childhood programs. National Louis University

- McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. (2022). The relationship between global classroom and administrative quality: A cross-cultural comparison. Research Notes. National Louis University.

- Raduan, N. A., & Na, S. I. (2020). An integrative review of the models for teacher expertise and career development. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 428–451.

- Rafanello, D. & Bloom, P. (1997, August). The 1997 Illinois Directors’ Study. A Report to the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.

- Rohacek, M., Adams, G. C., & Kisker, E. E. (2010). Understanding quality in context: Child care centers, communities, markets, and public policy. The Urban Institute.

- Sims, M., Forrest, R., Semann, A., & Slattery, C. (2014). Conceptions of early childhood leadership: driving new professionalism? International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(2), 149–166.

- Talan, T., N., Bloom, P. J, & Kelton, R. (2014). Building the leadership capacity of early childhood directors: An evaluation of a leadership development model. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 16.