BY McCormick Center | December 8, 2014

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

A recent report by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages,¹ highlights the relationship between poverty-level wages and high turnover among early childhood teachers. High turnover in early childhood programs disrupts center operations, alters the workplace environment, and affects the quality of teaching. But low wages are not the only influence on teachers’ decisions to leave their programs or the field. Teacher burnout is also a contributing factor to the high turnover rate in the early childhood field.

Burnout was the focus of a recent study of 108 early childhood teachers conducted by Konstantina Rentzou in Greece. The purpose of the research was to determine the extent to which teachers experience burnout and the degree to which the work environment contributes to the dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.²

Emotional exhaustion occurs when teachers feel worn out or depleted with little expectation that their emotional tanks can be replenished. Teachers may feel depersonalized if the social environment of their workplace is negative, cynical, or dehumanized. When teachers feel they are not effective in their work with children and families or dissatisfied with their job performance, the reduced sense of personal accomplishment can also result in burnout.

Early childhood teachers are especially vulnerable to burnout because they may work long hours, isolated in classrooms with little other adult interaction, or may not receive feedback and support from their supervisors.

SAMPLE AND METHODS

The sample was comprised of 46 kindergarten teachers and 62 child care workers. Eighty-nine percent of participants reported receiving formal training with a specialization in early childhood education.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory—Educators Survey (MBI-ES)3 was used to assess three dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. Reliability of the instrument was examined with these data yielding 0.81 Cronbach alpha value.

Twenty-one indicators from the Parents and Staff subscale of the Environment Rating Scale Self-Assessment Readiness Checklist (ERS-SRC)4 were used to measure the work environment. These indicators related to the physical and social nature of the early childhood work setting. Each indicator was rated on a 3-point scale from not met to fully met. The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was 0.86 for these data.

The researchers conducted a number of analyses including crosstabs, multiple hierarchical regression, ANOVA, t-tests, and stepwise correlations. Bivariate correlation analysis was used to examine whether the mean score assigned to the work environment indicators predicted the mean scores for each of the MBI-ES subscales.

RESULTS

While the overall scores from the work environment ratings did not predict burnout, items from bivariate correlation analysis between the work environment and each of the MBI-ES subscales yielded some significant correlations. Of the three dimensions of burnout, emotional exhaustion was the most highly associated with the work environment.

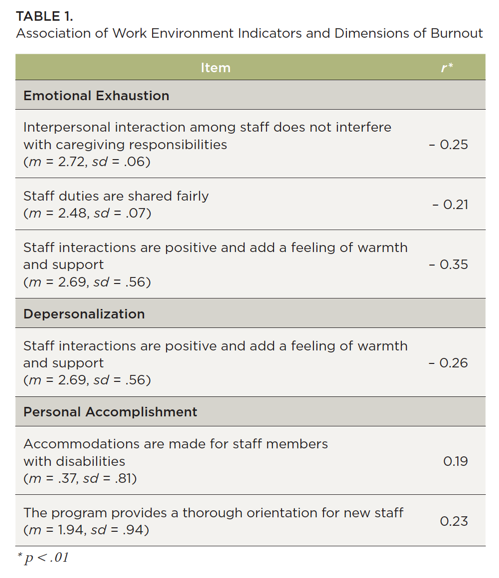

Significant negative associations were found for three indicators of the work environment related to emotional exhaustion: interactions among staff not interfering with caregiving, positive staff interactions, and equitable sharing of staff duties. Depersonalization was also negatively correlated with positive staff interactions. Personal accomplishment was positively associated when teachers reported that accommodations were made for staff members with disabilities and a thorough orientation for new staff occurred in their programs. Table 1 shows the strength of the correlations related to the three dimensions of burnout.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY, PRACTICE, AND RESEARCH

Emotional exhaustion takes its toll when teachers experience prolonged work-related stress with no anticipation of relief. If negative workplace conditions exist, it is not surprising that burnout can occur. When teachers experience warm, friendly, supportive, and trusting collegial relationships, they are more able to focus on the needs of the children. The findings of this study suggest that when teachers’ interactions with one another do not interfere with their caregiving responsibilities, they may be less likely to experience emotional exhaustion.

Results of this study also suggest that inequitable sharing of staff duties is another dimension of the work environment associated with emotional exhaustion. Early childhood program administrators need to understand the importance of fairness and equity when assigning work responsibilities. When teachers feel that they are required to do more than others, they are more likely to feel depleted and overworked.

In contrast, when the overall workplace climate is positive and teachers feel connected and supported, they may be less likely to experience burnout. This is suggested in the findings that measured both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. While many factors—both in and apart from the workplace—can lead to burnout, the moderate association of positive climate and support indicate that they may help to decrease its incidence.

Finally, there is a relationship between staff members’ sense of personal accomplishment and certain factors related to program management. Organizational policies and processes such as making accommodations for staff with disabilities or consistently implementing a thorough orientation process may influence if teachers experience burnout.

This study adds to our understanding that the dimensions of workplace climate are linked to the emotional wellbeing of staff. Goal consensus and clarity about procedures and responsibilities foster organizational norms where staff are careful that their interpersonal interactions do not interfere with their caregiving responsibilities. Program directors can also make adaptations to the physical layout and staffing schedules to promote collegiality, fostering positive staff interactions that are warm and supportive. Leaders who focus on the dimensions of organizational climate like task orientation and reward systems are concerned with equity and fairness in designing systems that lead to efficiency and program effectiveness.5

More rigorous research is needed to fully understand the causal effects of the early childhood work environment on staff burnout and occupational stress. Skillful program management and effective leadership are needed to create places where early childhood staff are supported, burnout is minimized, and turnover is reduced.

REFERENCES

- Whitebook, M., Phillips, D., & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy work, STILL unlivable wages: The childhood workforce 25 years after the National Child Care Staffing Study. Berkeley, CA: The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

- Rentzou, K. (2012). Examination of work environment factors relating to burnout syndrome of early childhood educators in Greece. Child Care in Practice, 18(2), 163–181.

- Kokkinos, C.M. (2002). Malsach Burnout Inventory for Educators. In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Psychometric Instruments in Greece (pp. 224–225). Athens: Ellinika Grammata.

- Center for Early Childhood Professional Development. (2003). Environment Rating Scale Self-Assessment Readiness Checklist. Retrieved from http://www.partnershipforchildren.org/pdfs/jts-ers-readicheckchildcarectr.pdf

- Bloom, P. J., Hentchel, A., & Bella, J. (2010). A great place to work: Creating a healthy organizational climate. Lake Forest, IL: New Horizons.