BY McCormick Center | March 17, 2015

Sim Loh is a family partnership coordinator at Children’s Village, a nationally-accredited Keystone 4 STARS early learning and school-age enrichment program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, serving about 350 children. She supports children and families, including non-English speaking families of immigrant status, by ensuring equitable access to education, health, employment, and legal information and resources on a day-to-day basis. She is a member of the Children First Racial Equity Early Childhood Education Provider Council, a community member representative of Philadelphia School District Multilingual Advisory Council, and a board member of Historic Philadelphia.

Sim explains, “I ensure families know their rights and educate them on ways to speak up for themselves and request for interpretation/translation services. I share families’ stories and experiences with legislators and decision-makers so that their needs are understood. Attending Leadership Connections will help me strengthen and grow my skills in all domains by interacting with and hearing from experienced leaders in different positions. With newly acquired skills, I seek to learn about the systems level while paying close attention to the accessibility and barriers of different systems and resources and their impacts on young children and their families.”

This document may be printed, photocopied, and disseminated freely with attribution. All content is the property of the McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership.

This resource is part of our Research Notes series.

Initiatives to improve administrative practices in early childhood programs take many forms. Some models are high-intensity, providing substantial external support for directors—formal training leading to an advanced degree, high dosage of technical support for achieving accreditation, and on-site coaching addressing multiple facets of program leadership and management. These high-intensity models have been shown to yield significant improvements in program- and classroom-level quality, organizational climate, and participants’ level of knowledge and demonstrated skill.1

Other models are moderate-intensity, providing a lower dose of formal training and on-site support, and lead to a director credential. Although the outcomes are not as robust as the high-intensity models, moderate-intensity initiatives also yield significant improvements in program quality and directors’ level of competency.2

Because high- and moderate-intensity initiatives are costly to implement, the current study examined an informal low-intensity approach to strengthening leadership capacity as a viable alternative.

THE MODEL

Beginning in 2006, the Metropolitan Council on Early Learning (MCEL), a program of the Mid-America Regional Council in Kansas City, offered a director support program with the following characteristics:

- Programs were assessed using the Program Administration Scale (PAS) to identify areas of administrative practice in need of improvement.3

- Facilitated cohort groups of directors met monthly for networking and peer support.

- Some training was offered to enhance leadership and management skills.

- Some coaching was provided to help directors develop and implement their program improvement plans.4

- Print and electronic resource materials were provided.

SAMPLE AND METHODS

Twenty-nine early childhood directors participated in two cohorts of the MCEL Director Support Program. Twenty-three participants (79%) completed the 18-month intervention. Participants in the sample were not highly qualified. Only one director had an advanced degree. More than half had not achieved an associate’s degree with 21 s.h. of college credit in ECE/CD and 9 s.h. in management coursework.

Participants were selected to represent a variety of early childhood centers in the Kansas City bi-state area. On average, the centers had a license capacity of 88 with 16 staff members. Fourteen programs (61%) were private nonprofit; 7 programs (30%) were private for-profit; and 2 (9%) were public programs. Three programs received Head Start funding. Nearly half of the centers (48%) were accredited.

Pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted by independent certified PAS assessors.5 Paired sample t-tests were performed to assess change over time for each center’s overall PAS score and individual PAS items 1 through 21. Staff qualifications were not included in the analysis. Cohen’s d was computed to assess effect size.

RESULTS

On average, the overall PAS scores improved for participants’ programs. There was a significant difference between the pre-intervention PAS scores (M = 2.87, SD =1.06) and the post-intervention scores (M = 3.47, SD = 1.14, t = 3.07, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .54) indicating a medium effect.

The average PAS scores for these items were compared to the national averages obtained from the normative samples in developing the PAS. Study participants scored lower than the national average when they began meeting with other directors. By the end of the study, the average scores for these items exceeded the national means.

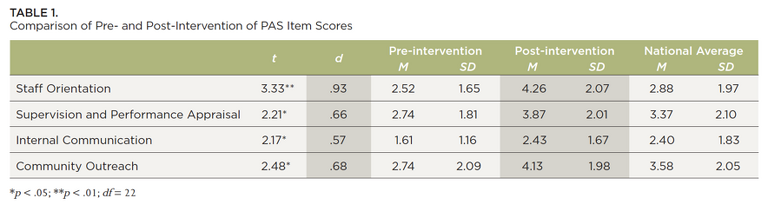

Significant differences were also found in four of the individual PAS items as seen in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that an informal low-intensity model may be a cost-effective means for yielding moderate positive outcomes in the administrative practices in early care and education programs.

Utilizing an assessment tool of leadership and management practices like the PAS provides structure and standards to guide directors, coaches, and peer mentors in identifying specific areas of strength and areas in need of improvement. A learning community offers a venue for discussing specific aspects of leadership and management practice and for exploring practical solutions to issues that directors experience.

Multiple intervention strategies were incorporated in this model including facilitated peer learning groups that met quarterly, two targeted training sessions per cohort, monthly coaching contacts to develop and execute improvement plans, and support with resources and formal education.6 The training topics emerged from the peer learning groups based on the initial PAS results and participants’ perceived needs. Coaches helped directors interpret PAS scores as well as understand the value of implementing management practices, documentation, and organizing materials and records.

Results suggest that the model may be more effective with certain dimensions of early childhood program administration than others. The large effect size (.93) for improvement in the PAS item assessing staff orientation practices indicates it was especially impacted by this initiative. Moderate effects were also seen in supervision and performance appraisal, internal communication, and community outreach. These aspects of leadership and management can be readily adjusted by program directors, which may explain why the effects are more significant than for other areas that involve many individuals affiliated with the organization.

Many state leaders overseeing early childhood quality initiatives are considering how to take successful program models to scale or how to sustain advances made in statewide systems. Initiatives implementing a facilitated peer learning model for improvement in administrative practices may offer cost-effective features that could be incorporated into larger system initiatives such as QRIS. Participant cost data was not available for this study, but the intervention model using peer supports may be more feasible than other models that incorporate extensive formal training.

There are several limitations to this study that should be considered in interpreting the results. Caution should be exercised in generalizing the results due to the small sample size. Multiple aspects of the intervention model were not evaluated independently requiring further research to determine which strategies most contribute to its effectiveness. Its applicability to other agencies and in diverse communities is also unknown, although other low-intensity leadership training programs have reported similar results. The results of this study suggest that additional research on the intensity of professional development for early childhood administrators is warranted.

- Bloom, P. J., & Sheerer, M. (1992). The effect of leadership training on program quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 7(4), 579-594.

- Bloom, P. J., Jackson, S., Talan, T. N., & Kelton, R. (2013). Taking Charge of Change: A 20-year review of empowering early childhood administrators through leadership training. Wheeling, IL: McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership, National Louis University.

- Talan, T. N. & Bloom, P. J. (2004). Program Administration Scale: Measuring early childhood leadership and management. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Meeting facilitation, training, and coaching were provided by Francis Institute for Child and Youth Development, located at Metropolitan Community College-Penn Valley.

- Assessments were conducted by University of Missouri-Kansas City, Institute for Human Development.

- Newkirk, M. K. (2014, January). Improving leadership and management practice in early learning programs through assessment and support. University of Missouri-Kansas City Institute for Human Development.